compiled and edited by Matt Leivers and Andrew B. Powell with contributions by by Martyn Barber, Mark Bowden, Rosamund J. Cleal, Nikki Cook, Mark Corney, Paul Cripps, Andrew David, Bob Davis, David Dawson, Bruce Eagles, Jane Ellis-Schön, A. P. Fitzpatrick, Abigail George, Frances Healy, Katie Hinds, David Hinton, Ronald Hutton, Mandy Jay, Matt Leivers, Michael Lewis, Rebecca Montague, Janet Montgomery, David Mullin, Joshua Pollard, Melanie Pomeroy-Kellinger, Andrew B. Powell, Andrew Reynolds, Clive Ruggles, Julie Scott-Jackson, Sarah Simmonds, Nicola Snashall, Chris J. Stevens, Anne Upson, Bryn Walters and Sarah F. Wyles.

by Julie Scott-Jackson

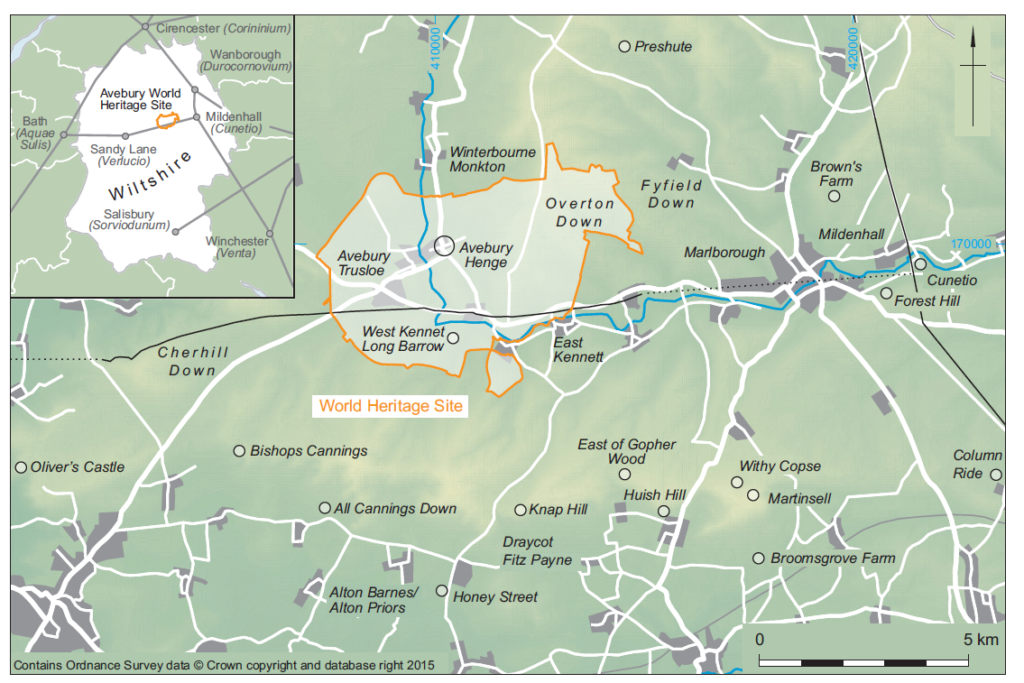

The chalk downlands, which topographically characterise the Stonehenge and Avebury WHS in Wiltshire, stretch through 12 counties of southern England. Invariably these downlands are capped, on the highest parts, with deposits mapped as Clay-with- flints. Over the past 100 years or so, a great number of Lower and Middle Palaeolithic stone tools have been found in association with these deposits. The recorded evidence of the Upper Palaeolithic is almost non-existent but this may be due in part to misidentification of such artefacts with those of the Late Middle Palaeolithic and Early Mesolithic.

There has been lack of appropriate research and a general misunderstanding regarding both the archaeological integrity of the Palaeolithic artefacts from high-level sites on deposits mapped as clay- with-flints, and the geomorphological processes that have operated in areas of chalk downlands, on these specific deposits, over geological time. As a result, these high-level assemblages are poorly represented in the British Lower and Middle Palaeolithic archaeological record. Those Palaeolithic sites which are datable and/or provide the best examples of Palaeolithic industries must command the greatest attention. But site-specific data do not necessarily address the questions of Palaeolithic peoples’ habitat range and preferences, and their provision of resources across the landscape. If the behavioural organisation of these ancient hunter-gatherers is to be understood then the Palaeolithic landscape must be considered as a whole. Failure to do so will distort both the local and national archaeological record.

Sometime during the Pleistocene period, Palaeolithic people first arrived in what is now Britain. This geological period was one of glacial and interglacial cycles. Ice-sheets advanced or re-treated, sea-levels rose and fell. When sea-levels were high, Britain became an island but when sea-levels were low land linked southern England to continental Europe, thereby allowing the migration of animals and Palaeolithic people across the peninsula. The Wiltshire region was never affected by direct glacial activity as the area lay beyond the ice-sheets. But weathering processes operating during the Pleistocene glacial and interglacial cycles effected considerable changes to the topography of the Stonehenge and Avebury area (Kellaway 1991; 2002). The two geomorphological (weathering) processes which dominated in the Pleistocene were periglaciation, during cold periods, and that of solution when the climate ameliorated. Often the effects of periglaciation have been confused with those of solution (Williams 1980; 1986; Scott-Jackson 2000; 2005, 66–7; Geddes and Walkington 2005, 63–4) with the result that the archaeological integrity of the Palaeolithic find sites/spots, particularly on deposits mapped as Clay-with-flints, and the artefacts they contain have been academically devalued.

Significantly, it is the presence of ‘pipes’ and ‘basin- like’ features in the deposits mapped as Clay-with- flints (which are produced in response to the process of dissolution in the underlying chalk) that has been instrumental in retaining the Clay-with-flints deposits and the associated Palaeolithic sites and artefacts on the highest downland hilltops and plateaux, over hundreds of thousands of years (for examples see: Smith 1894; Scott-Jackson 2000; 2005; Harp 2005; Scott-Jackson and Scott-Jackson 2014). The importance of the Palaeolithic archaeological potential within the high-level Clay-with-flints deposits and also at lower levels (in a variety of soils, see for example: Richards 1990, 6–7; Findley et al. 1984) in the WHS of Stonehenge and Avebury needs due consideration. This is particularly true if embedded artefacts are found, as many of these finds have proved to be discrete assemblages that are indicative of in situ Palaeolithic sites.

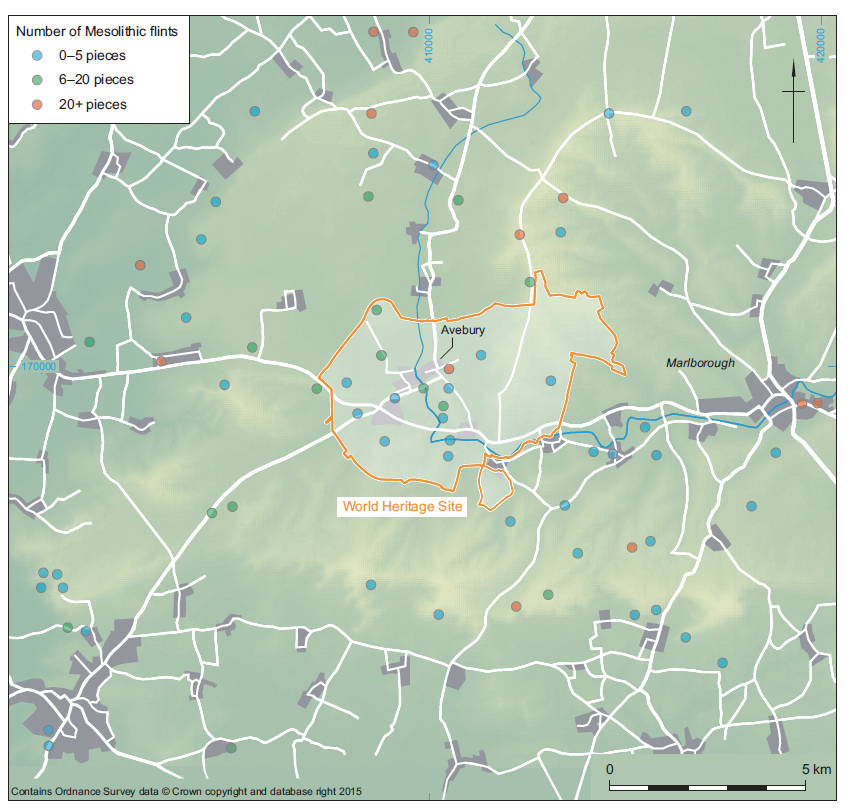

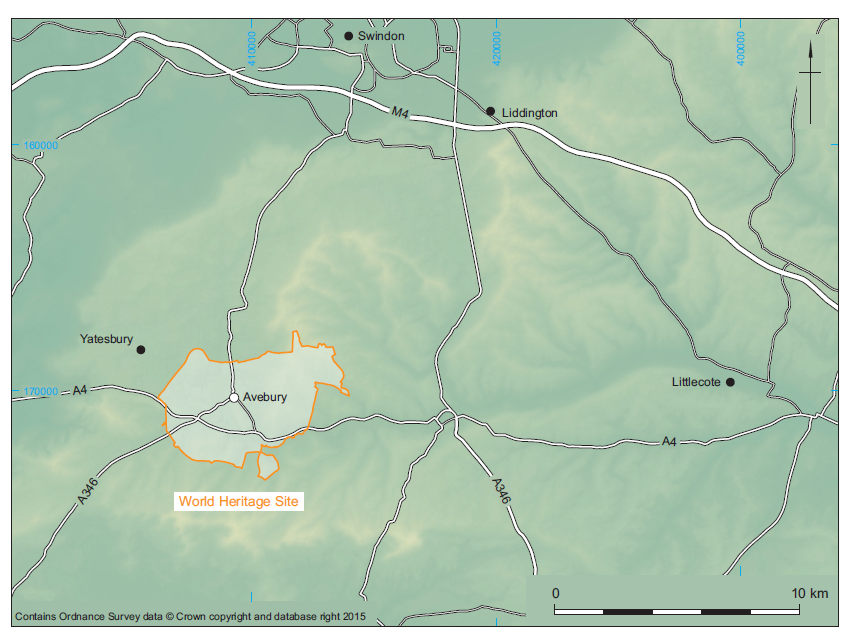

Detailed geological, geomorphological and archaeological investigations of Palaeolithic find- spots/sites across the Marlborough Downs and Avebury area (Fig. 10) have been carried out (Scott- Jackson 2000, 53–66; 2005, 67–76). Although the majority of these recorded artefacts can be viewed only as single isolated surface-finds, a number of find- spots appear to have a geomorphological relationship (eg, on top of a hill and on the slope of the same hill). This does not of course imply that there is an actual association between the artefacts but their geomorphological relationship may help to explain the processes through which each artefact assumed its recorded location, as for example on a slope, relative to its originating location, a knapping site on a hill-top (Scott-Jackson 2000, 16–18). There are in total 39 recorded Palaeolithic find-spots/sites across the Marlborough Downs. Of these, 14 find-spots/sites are within a 5 km radius of Avebury village (Fig. 10). Full entry details and discussions on all 39 find-spots/sites may be found in Scott-Jackson 2005 (67–76).

Most of these Palaeolithic artefacts are held in either the Devizes or British Museums; the whereabouts of the others remains unknown. The majority of the artefacts are reported as being single surface finds from the topsoil overlying the downlands (many sites may well have been lost as Palaeolithic artefacts, particularly waste-flakes, are not always recognised for what they are). The most important of the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic finds from the Avebury area (just outside the WHS) are those from the site on Hackpen Hill (SU 128726), a site which was excavated with great care by H. G. O. Kendall (see Kendall 1909; 1916); the artefacts were re-assessed by A. D. Lacaille (1971) and the site and artefacts reinvestigated by J. E. Scott-Jackson (2000, 53–66) whose investigation also corrected data distortions and addressed NGR anomalies.

A site outside the WHS (15 km east from Avebury village) also requires special mention. The low-level Palaeolithic site at Knowle Farm, Gravel Pit, Savernake, is situated in soliflucted head gravel. Investigated/excavated by Cunnington and Cun- nington (1903); Dixon (1903); Kendall (1909; 1911) and Froom (1983, 27–37) it produced over 2000 Palaeolithic artefacts, mainly handaxes (for detailed discussion see Scott-Jackson 2005, 71); Wymer (1993, 57) noted that ‘only sporadic finds have been made since’. More recently Palaeolithic artefacts (two handaxes and four flakes) have been discovered in shallow quarrying of valley gravels, in the valley opposite Knowle Farm, Little Bedwyn, Savernake, at SU 256 678 (A) (132 m OD).

Both ancient and modern river valleys, stream channels and (to a lesser extent) dry valleys have produced a great number of Palaeolithic artefacts. The associated river gravel, alluvium and valley gravel in these low-level downland areas include materials (and artefacts) that have been washed down from higher levels. Colluvium fills the dry-valleys, while much of the river gravel is of Pleistocene age, often overlain and replenished with reworked materials (including artefacts) of various origins and ages. Stone tools recovered both as surface-finds (ie, mixed in with the gravel) and from very shallow gravel deposits are therefore almost certainly in a derived context. Although the potential for the survival of in situ sites in river and valley deposits is high, few excavated sites have been found to be in situ, most of the artefacts being derived. Nevertheless, some of the most important Palaeolithic in situ sites in Britain have been found in a variety of low-level deposits (frequently gravels, but not specifically in downland areas (eg, Wymer 1999).

by Abigail George

This section covers the end of the Pleistocene during a period between the last glacial maximum at around 16,000 cal BC and the beginning of the Neolithic in Britain, around 4000 cal BC. It covers an initial period of climatic oscillation, between extreme cold snaps and rapid warming, followed by a gradual rise in temperature towards the so-called Climatic Optimum of the mid- to Late Mesolithic, and terminating with a slow amelioration during later prehistory.

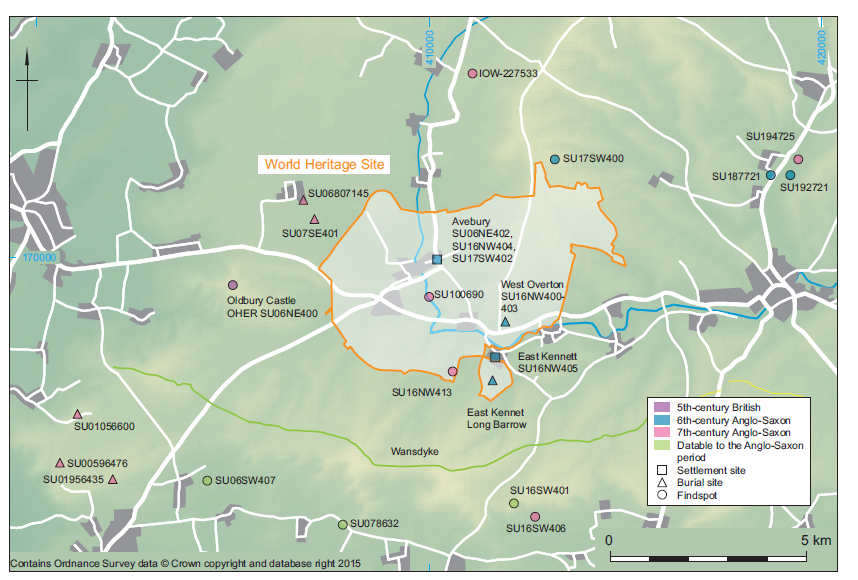

There are 11 finds – all lithics – noted in the HER as being ‘Palaeolithic’ within 20 km2 around Avebury. However, none of these are assigned to the Upper Palaeolithic and at the present time there are no definite Upper Palaeolithic sites or findspots within the WHS (Scott-Jackson 2005; Pollard and Reynolds 2002; see Scott-Jackson, above). It is, however, possible that the Avebury area was exploited to some extent by human populations during the Late Glacial as there is clear evidence for sustained use of the lower River Kennet Valley (Froom and Cook 2005).

The Early Post-Glacial period refers to a time after c. 7750 cal BC when the tool technology began to change to a broad blade microlithic industry (Jacobi, 1976). Pollen and molluscan studies have indicated that closed woodland existed around the Avebury area (Evans 1972) although Allen (2005) suggests that within this woodland large natural clearing may have been the focus for settlement and community. Whittle (1990) proposes that the downland and upper dip- slope valley were seldom used and that the main base camps were likely to be outside the area, suggesting Cherhill and the Wawcott as possibilities. He suggests that a territory of at least this size is plausible – a distance of 40 km along the River Kennet.

There are a small number of findspots and sites within the WHS (Fig. 11), only two of which (Rough Leaze and Avebury) can be described as minor (short stay) occupation sites. Again, it is possible that the Avebury area was exploited by human groups since there is a good deal of occupation evidence for Early Post-Glacial sites in the Kennet Valley (Froom 1963; 1965; 1970; 1972a; 1972b; 1976; Froom and Cook 2005; Sheridan 1967; Wymer 1962; Churchill 1962; Heaton 1992).

Whilst these sites are not local to the Avebury WHS, it is not inconceivable that these and other sites within a few days walking distance formed part of a wider Mesolithic territory around the lower and middle Kennet Valley. The importance of the River Kennet as a tributary of the River Thames should not be underestimated. The area around Avebury prior to 6550 cal BC was probably not a place in isolation, but was rather linked to the rest of southern England and the Continent via a Kennet–Thames–Rhine routeway. In addition, routes to the south coast via the Hampshire Avon and to the Severn Estuary in the west via the Bristol Avon all lead to key Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic sites in the Severn Estuary (Bell 2007) and at Hengistbury Head (Barton 1992).

According to Smith (1992), hunter/fisher/gatherer populations would have been of a very low density, perhaps as few as 20 people in a 200 km2 area at any one time, although Rowley-Conwy puts this at a higher density of between 45 and 120 people (Rowley-Conwy 1981). In order to annually sustain such group numbers various sections of the Avebury landscape would have been seasonally utilised. It is therefore essential that any future research agenda for this period encompass a much wider geographical area than the current boundaries of the WHS. For this purpose an area of 20 km2, with Avebury as its centre, has been taken to establish a more realistic perspective on the early prehistoric human exploitation of the landscape (see Fig. 11). This is still somewhat limiting as it does not include the Kennet Valley sites mentioned above. However, it is beyond the scope of this paper to encompass the full territory that may have been utilised, which may also have included sites along the River Og at Marlborough and those tributaries around Hackpen Hill and Aldbourne. These sites may be an important link between Avebury and the Wawcott sites and should be considered as part of a wider contextual assessment of the Wiltshire landscape.

Early land-use during the Late Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic may well have been preludes to the development of the later prehistoric landscape. A clear example of this is the large timber (‘totem’) posts that were discovered in the Stonehenge car park (Vatcher and Vatcher 1973; Allen 1995; and a more recent find at Amesbury Down, see Allen and Gardiner 2002; Powell and Barclay forthcoming). In addition, Mesolithic flints are often found under Neolithic monuments suggesting a history prior to the first pastoralists. However, the ephemeral nature of these finds is frustrating and until further well-stratified sites are discovered we can only speculate as to whether these are just residual finds or something more significant. Another approach, explored by McFadyen (2006) is to look at exploring the nature of such ephemeral finds in a more theoretical way: ‘spaces were actively being made … rather than simply inhabited as meaningful “places” ’; even small scatters of flint can tell us a great deal about the processes that people were undertaking, and the connections between the people and their environment (McFadyen 2006). Moreover, individual lithics and scatters can also say something about trade and exchange, power- relations between communities and the pathways they may have taken for these events to take place (Bradley 1993).

by Rosamund J. Cleal and Joshua Pollard, with Nicola Snashall and Rebecca Montague, and a contribution on Archaeoastronomy by Clive Ruggles

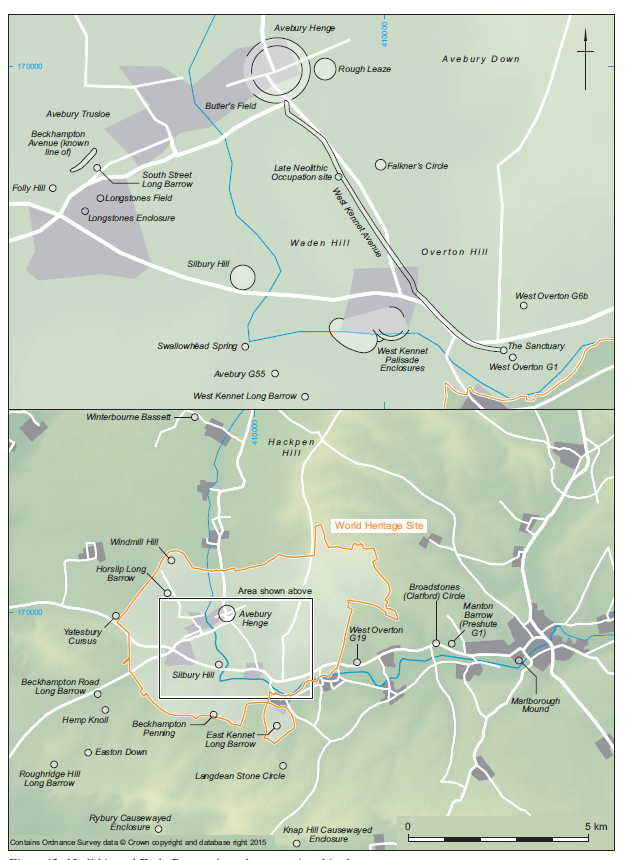

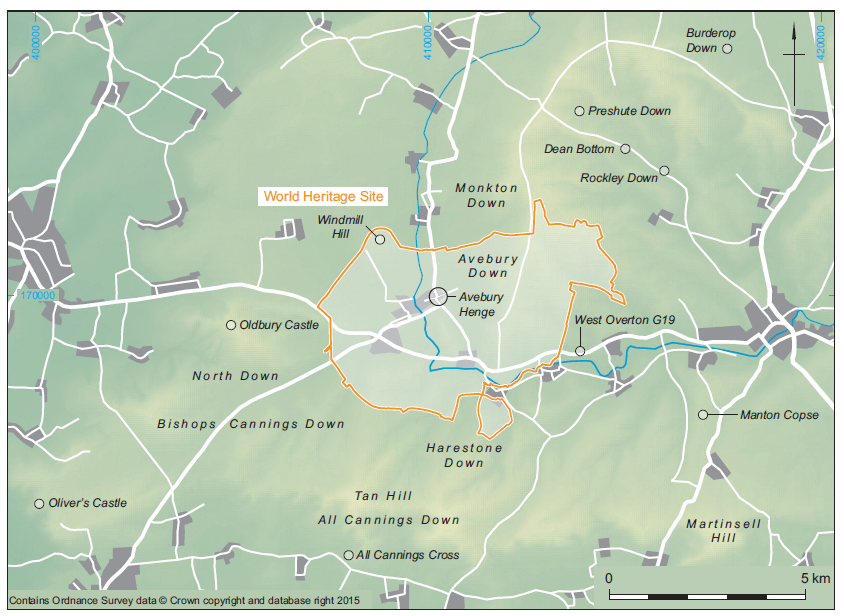

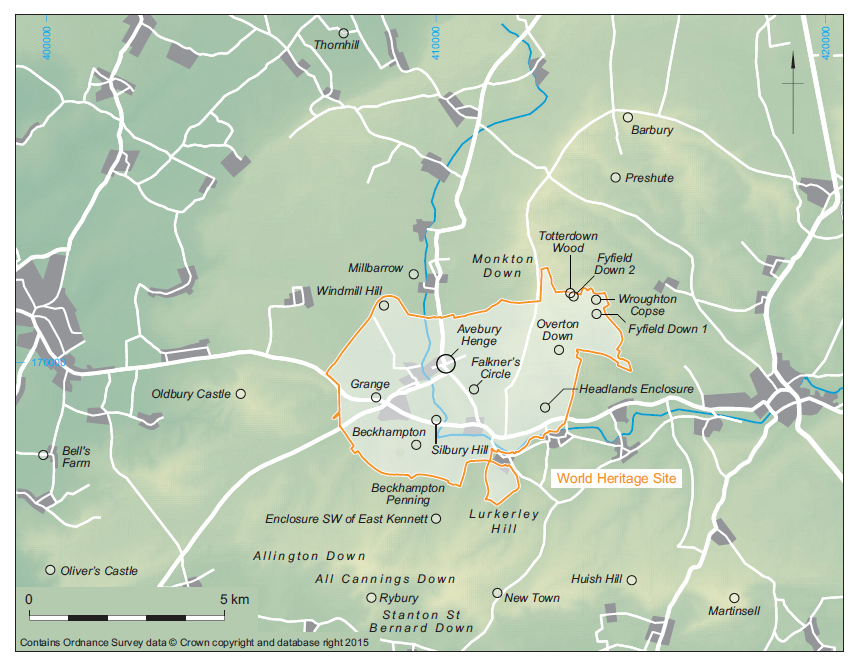

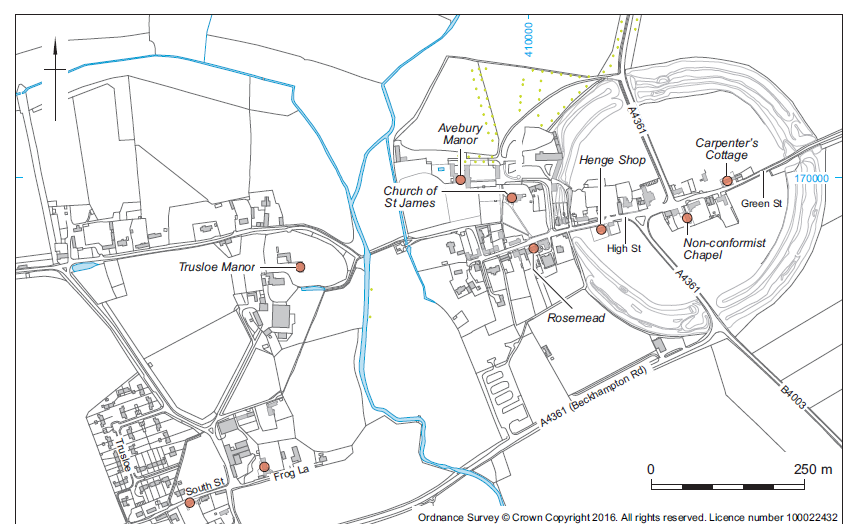

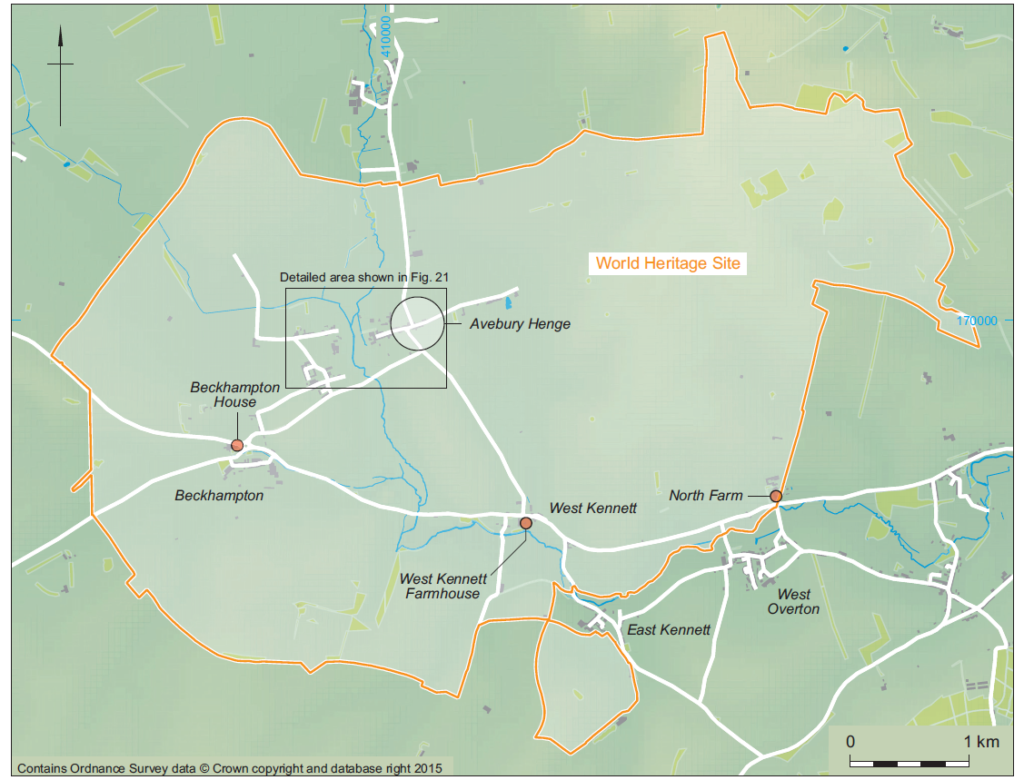

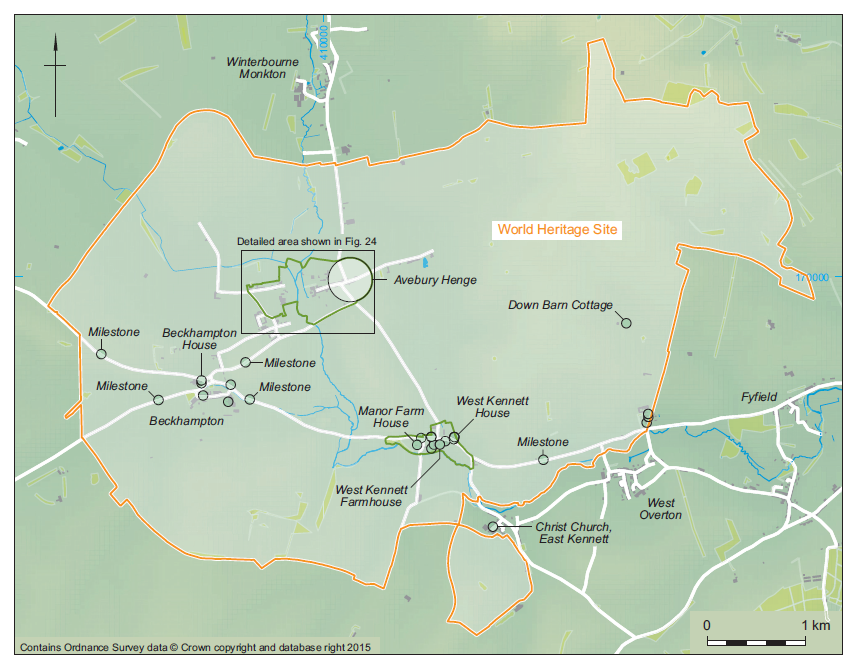

The archaeological significance of the Avebury landscape ultimately rests on the value ascribed to the great Late Neolithic monument complex that includes the Avebury henge, the West Kennet and Beckhampton megalithic avenues, the Sanctuary, West Kennet palisade enclosures and Silbury Hill. These monuments, along with earlier, 4th millennium cal BC, constructions such as the West Kennet long barrow and Windmill Hill enclosure are exceptional in scale and architectural complexity; and their presence is indicative of a social and religious pre-eminence to this region during the Neolithic on a par with that of the Stonehenge landscape (Fig. 12). These monuments continue to occupy a key position in our accounts of the period on a national and international scale because of their potential to inform us of aspects of social and economic organisation, belief, ceremony and the material worlds of their builders.

Chronological frameworks are discussed elsewhere in this volume by Frances Healy. It is sufficient here to note that the transition to Neolithic practices and ways of life in the Avebury area came later than that in the Lower and Middle Thames Valley and perhaps the Cotswolds, within the range 3975–3835 cal BC at 95% probability (Whittle et al. 2011). This provides the upper limit for the chronological span considered in this section, while the lower limit is given by the transition to the agrarian landscapes of the Middle Bronze Age at around 1500 cal BC. Both upper and lower limits, however, need to be treated as approximate.

Archaeological activity within the WHS was intense during the 20th century, following two and a half centuries of antiquarian activity centred largely on the henge and Early Bronze Age round barrows. Previous archaeological and antiquarian activity is described elsewhere (Smith 1965b; Pitts 2000; Pollard and Reynolds 2002; Gillings and Pollard 2004), although more detailed outline histories of investigation are provided here for key monuments such as the Avebury henge. Discussion is structured thematically, beginning with the evidence for early 4th to early 2nd millennium cal BC settlement and landscape use, followed by reviews of material culture, lifeways, and monumentality. Where their significance impacts on understanding of the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age archaeology of the WHS, a small number of sites outside the area are referred to.

Because of the absence of any sustained Late Mesolithic presence in the region, it has been argued that the onset of the Neolithic was marked by the arrival of incoming groups, either from neighbouring areas or much further afield (Whittle 1990, 107). It was during the early 4th millennium cal BC that the environment of the Avebury landscape was first subject to major human modification, through more extensive and sustained settlement, clearance, agriculture and monument building. By the second and third quarters of the 4th millennium cal BC occupation within the region was extensive, though not necessarily dense. Traces of settlement activity and agriculture are relatively ephemeral, comprising surface scatters of worked flint and occasionally pottery, more substantial remnants of middens, pits, and post and stake settings, along with cultivated soils. The absence of any solid ‘domestic’ architecture is taken to indicate varying degrees of settlement permanence/impermanence, which could range from strategies of short-lived sedentism to seasonal transhumance (Whittle 1997b; Edmonds 1999; Pollard 1999a). Following a pattern seen repeatedly across southern England, it is only from the mid-2nd millennium cal BC that stable agricultural settlements and field systems appear.

Topsoil/ploughsoil scatters of worked flint and casual finds of lithics and ceramics provide the best evidence for the presence and extent of settlement and associated activity (Holgate 1987; 1988; Whittle et al. 2000). Many of the larger scatters that have been identified are located on the upper slopes and higher ground around the main monument complex – effectively ‘looking in’. The lithics contained within them indicate that some have formed through repeated visitation over long periods of time (eg, the southern slope of Windmill Hill), while others are dominated by distinctive Middle–Late Neolithic tool forms (eg, foot of Avebury Down). Further details are provided by Snashall, see above.

In addition to finds made during surface collection, traces of Neolithic and Early Bronze Age occupation have been encountered fortuitously during groundworks and in the excavation of contemporary monuments and later sites. A limited amount of research-led excavation has also focused on identifying settlement evidence (Whittle et al. 2000; Pollard et al. 2012). Traces here take the form of buried artefact scatters (including dense concentrations best interpreted as midden spreads), pits and other sub-soil features, fence-lines, artificial surfaces and cultivated soils.

Several scatters of worked flint and pottery in the buried soil under the bank and within the interior of the Avebury henge are the residue of episodes of pre- monument occupation (Gray 1935; Passmore 1935; Smith 1965b, 224–6; Evans et al. 1985). Over 100 sherds of pottery and 200 pieces of worked flint were recovered from these contexts. Associated ceramics range from early carinated bowls to Peterborough Wares, suggesting a chronological span that could take in the whole of the 4th millennium cal BC (supported by three radiocarbon dates relating to pre- henge activity: Pitts and Whittle 1992). From the buried soil profile under the henge bank come indications of associated clearance and cultivation. The environmental succession begins with Early Holocene woodland, followed by clearance at some stage during the Early Neolithic, then cultivation and the formation of grassland (Evans et al. 1985; Evans and O’Connor 1999, 202–4). Cultivation included the use of an ard, uncommon on sites of this date though similar and more extensive ard marks of early– mid-4th-millennium cal BC date were recorded under the South Street long barrow (Ashbee et al. 1979). In the immediate zone to the east of the henge, topsoil sampling and limited excavation in Rough Leaze during 2007 identified scatters of worked flint that included material of possibly Late Mesolithic and certain Early and Middle Neolithic dates, a series of Early Holocene tree-throw holes containing small quantities of artefactual material within their upper fills, and one location where there exists a concentration of stakeholes likely associated with prehistoric activity (Pollard et al. 2012).

To the south and south-east of the henge there are several localised scatters of earlier Neolithic worked flint, pottery, pits and midden deposits along the sides and base of the dry valley formed by Waden Hill and Avebury Down/Overton Hill, and on Overton Hill itself (Smith 1965b, 210–16; Thomas 1955; Snashall 2007; Gillings et al. 2008). Several pits and postholes were found during the 1930s work on the West Kennet Avenue amongst a substantial ‘midden’ spread of flint and pottery (Smith 1965b). The range of ceramics from the site (Ebbsfleet, Mortlake, Fengate and Grooved Wares) show occupation, if intermittent, spanning the latest 4th to early/mid-3rd millennia cal BC, before the West Kennet Avenue was built. Just to the north, a small pit containing sherds of Mortlake bowl was encountered during cable work close to stone 16a of the West Kennet Avenue (Allen and Davis 2009). This pit was dated to 3090–2910 cal BC; with mollusca indicating a predominantly open yet still mosaic environment. More difficult to characterise are concentrations of 4th millennium cal BC ceramics (Plain and Decorated Bowl and early Peterborough Wares) on Overton and Hackpen Hills, associated with small amounts of worked flint and some animal bone, but no evident structural features (Smith and Simpson 1964; 1966; Snashall 2007). The relative scarcity of associated lithics and structural features is at odds with the scale of some of these ceramic assemblages (eg, that under West Overton G6b: Smith and Simpson 1966), implying occupation of a different kind – or at least a different suite of activities – on the high ground to that along the valley sides and floor.

Isolated pits and small pit clusters of Neolithic and Beaker date are also known from Windmill Hill (predominantly Early Neolithic, and some pre- enclosure; Smith 1965b); from its southern slope (one cluster associated with Plain Bowl pottery, two other pits with Grooved Ware; Whittle et al. 2000); from Avebury G55, close to the West Kennet long barrow (Smith 1965b); and outside the WHS on Hemp Knoll (Robertson-Mackay 1980) and Roughridge Hill (Proudfoot in prep.). The latter may belong to the first quarter of the 4th millennium cal BC and so an early phase of settlement within the region, the pits’ contents included, unusually, human bone along with a range of ceramics, lithics and animal bone.

House sites of the period remain elusive. Stakehole arrangements and pits probably mark their former presence in many instances. There are hints that better preserved house structures might be found. Artificial chalk surfaces found during coring against the southern bank of the Avebury henge, here buried by colluvium (Allen and Snashall 2009), and under a midden spread at the West Kennet palisade enclosures (Whittle 1997a, 12, 76, fig. 43) look tantalisingly similar to the puddled chalk floors of houses at the Late Neolithic settlement at Durrington Walls (Parker Pearson 2007).

Beyond palaeo-environmental investigations by John Evans, and those undertaken by English Heritage as part of the Silbury Hill project, little work has taken place in the floodplains of the Winterbourne and Kennet, though these are locations where settlement evidence might be expected and where later colluvial cover should provide good preservational conditions. Potential is shown by test trenching in Butler’s Field to the west of the henge where earlier Neolithic flintwork and pottery were found within buried soils (Evans et al. 1993). The likelihood of there being sizeable spaces ‘empty’ of occupation must, however, be considered, and is hinted at by gaps in lithic scatter distributions. Along the whole length of the Avebury sewer trench there were virtually no Neolithic or Early Bronze Age finds, except for the location of a ‘lost’ disc barrow, although the conditions of recovery during the work may have contributed to this apparent absence (Powell et al. 1996, 82). Cable trenching across part of Avebury Trusloe and the northern half of Longstones Field during 2010 likewise yielded a virtual blank despite careful monitoring.

A lengthy history of archaeological investigation within the area of the WHS and its environs has resulted in the curation of a number of important assemblages of Neolithic and Early Bronze Age artefactual and faunal material. Setting aside for the present those from antiquarian investigation of the area’s round barrows, the singularly most significant assemblage derives from the enclosure on Windmill Hill (Smith 1965b; Whittle et al. 1999). The early 20th-century excavations here by Keiller provided stratified assemblages of ceramics (Pl. 23), lithics and other materials (worked chalk, worked bone, imported stone tools) that were instrumental in establishing material sequences for the southern English Neolithic, reflected in Stuart Piggott’s choice of the monument as the type site for his ‘Windmill Hill culture’ (Piggott 1954). That assemblage was augmented by material recovered in subsequent excavations in 1957–8 and 1988. A sense of scale can be gathered from the estimates of over 20,000 sherds of pottery from c. 1200 vessels, the majority Early Neolithic (Zienkiewicz and Hamilton 1999); and around 100,000 pieces of worked flint (Pollard 1999b). Other stratified assemblages of Early Neolithic material have come from the excavation of various pit groups (see above), and from the long barrows of West Kennet (Piggott 1962) and Horslip (Ashbee et al. 1979).

The substantial lithic assemblage from the West Kennet Avenue ‘occupation site’ includes a strong component of distinctive Middle Neolithic forms, including ‘Levallois-style’ cores, edge-polished pieces and chisel arrowheads (Smith 1965b). A remarkable assemblage from a little-understood phase within the region’s Neolithic, it would repay further analysis. That is also true of the Peterborough Ware and Late Neolithic–Early Bronze Age ceramics and lithics from the secondary fills of the chambers of the West Kennet long barrow (Piggott 1962), and from the adjacent ‘midden’ site of Avebury G55 (Smith 1965a). Remarkably little material was recovered during the 20th-century excavations at the Avebury henge (Gray 1935; Smith 1965b), especially when viewed in contrast to the substantial amounts of Grooved Ware and associated lithics and faunal material from Whittle’s excavations at the West Kennet palisade enclosures (Whittle 1997a). Smaller quantities of Grooved Ware have come from the excavation of pits, the buried soil under West Overton G6b (Smith and Simpson 1966), the Sanctuary (Cunnington 1931; Pollard 1992) and from the Longstones enclosure (Gillings et al. 2008) (see gazetteer in Cleal and MacSween 1999). Early funerary and non-funerary Beaker finds within the region have been recently reviewed by Cleal and Pollard (2012); while grave assemblages of the late 3rd and early 2nd millennia cal BC are the subject of overview in Grinsell (1957) and Cleal (2005). Of note is the important Beaker grave assemblages from West Overton G6b (Smith and Simpson 1966), East Kennet (Kinnes 1978) and immediately outside the WHS on Hemp Knoll (Robertson-Mackay 1980).

The original Archaeological Research Agenda for the Avebury WHS stressed the need to consider evidence for human health and diet, highlighting the potential that developments in aDNA, lipid and stable isotope analyses could offer, in addition to the data routinely obtained through osteological, faunal and palaeo- botanical work (Cleal and Montague 2001, 42–3). The potential of recently refined analytical techniques is beginning to be realised (eg, Copley et al. 2003; Haak et al. 2008; Smith and Brickley 2009); and the region possesses rich assemblages of well- contextualised Neolithic and Early Bronze Age human and animal bone, carbonised plant material, and ceramics that are suitable for such work (notably from Windmill Hill, the West Kennet palisade enclosures, and various barrow excavations). Analysis of lipids extracted from earlier Neolithic vessels from Windmill Hill has revealed a majority with traces of predominantly dairy fats (Copley et al. 2003). The mixing of ruminant and porcine adipose fats was also detected in individual vessels. Comparable analysis of Grooved Ware sherds from the West Kennet palisade enclosures showed a predominance of porcine adipose fats, providing good agreement with the balance of domesticated animal species represented among the faunal remains (Mukherjee et al. 2007).

Recent (re-)analysis has been undertaken on the human remains from a number of 4th-millennium cal BC sites in the WHS, notably Windmill Hill (Brothwell 1999), Millbarrow (Brothwell 1994), and the West Kennet long barrow (Bayliss et al. 2007a). An instance of trauma (healed fracture) was detected among the population at Millbarrow, along with a possible well-healed double trephination (Brothwell 1994). Wysocki’s work on the West Kennet long barrow remains shows that the scale of the primary mortuary deposit was previously over-estimated (now revised down to 36 individuals), but that many more adult and infant remains are present within the secondary deposits than indicated in the original report (Bayliss et al. 2007a). One individual in the NE chamber may have been killed by arrowshot (Piggott 1962, 25).

For the late 3rd and early 2nd millennia cal BC, there are good data on the age, sex and health of individuals buried at Avebury G55 (Brothwell 1992), West Overton G6b (Brothwell and Powers 1966), Overton Down (Rogers and Everton n.d.), and West Overton G19 (Wysocki, in preparation). Further information, particularly on diets and mobility, will come through the work of the ‘Beaker People Project’ (Jay et al. 2012). Of note is the evidence of vitamin/iron deficiency, linked perhaps to poor hygiene and other environmental stress, from an infant buried under Avebury G55 (Brothwell 1992).

It was through the creation of earthwork, timber and stone monuments that the geography of the region was to be radically transformed. Through their physical presence such monuments would endure, creating a lasting impact on the way in which subsequent generations would inhabit the landscape (Cleal and Pollard 2012). During the second and third quarters of the 4th millennium cal BC a series of long barrows and earthwork enclosures was constructed in localised woodland clearings, many in places which already possessed long histories of activity (Pollard and Reynolds 2002, 59–62; Whittle et al. 1999).

There are around 30 known megalithic and non- megalithic long mounds in the wider Avebury region (Barker 1985). Those with megalithic (sarsen) chambers are mostly located in the zone to the east of Avebury and share constructional traits with so- called Cotswold-Severn long barrows in regions to the north and west (Darvill 2004). Within the WHS are the chambered barrows of West Kennet and East Kennet, along with the likely site of the Beckhampton Penning barrow recorded by Stukeley, and the Horslip, South Street and Beckhampton/Longstones earthen long barrows. A further ploughed-down long barrow may exist just to the south-east of Avebury, being visible as an apparently U-shaped ditch on satellite imagery (Pl. 5). Of these, three have been excavated under modern conditions: West Kennet, South Street and Horslip (Piggott 1962; Ashbee et al. 1979). Just outside the WHS a further three long barrows have been excavated in the same time period: Beckhampton Road, Millbarrow and Easton Down (Ashbee et al 1979; Whittle et al. 1993; Whittle 1994). Excavation has revealed very different constructional details and sequences; a degree of diversity in fact typical of these monuments (Kinnes 1992; Darvill 2004). South Street and Beckhampton Road are most similar, with complex bayed mound construction displaying axial asymmetry, and in both cases without mortuary deposits. At South Street an irregular cairn of stones took the place where a wooden chamber might have been found. Deposits of human bone were also absent at Horslip, although the mound was very denuded by the time of excavation, and it cannot with confidence be stated that the barrow was without a mortuary function. Here a line of pits pre-dated the mound. Easton Down originally covered a restricted number of inhumations, perhaps within a timber- defined mortuary structure (Whittle et al. 1993). At Millbarrow human remains from the primary mortuary deposit survived within the disturbed area of the original chambers (Whittle 1994). Available radiocarbon dates suggest the South Street, Beckhampton Road, Easton Down and Millbarrow long barrows were relatively late creations, being constructed in the second half of the 4th millennium cal BC (Whittle et al. 2011, 103–5).

Excavation of buried soils and features under all of these mounds has revealed important sequences of pre-barrow activity – variously clearance, cultivation, plot division, temporary occupation, artefact discard, and even, in the case of Millbarrow, hints of earlier phases of human bone deposition – a reminder that their value as ‘islands’ of survival of high-resolution environmental data and ephemeral traces of human presence should never be ignored.

The most impressive and widely known of these monuments is that of West Kennet (Pl. 24), the site having an almost iconic status. Excavations took place in 1859 and 1955–6, the latter fully published by Piggott (1962), who gives a summary account of the earlier depredations and of the work by Thurnam (1867; Piggott 1962, 1–7). The finds are held by more than one museum or university: the artefacts are in Wiltshire Museum, the human skeletal remains in the Duckworth Laboratory of the University of Cambridge and the animal bones in the comparative series of the Department of Zoology of the Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh (Piggott 1962). Comprising a substantial chalk and sarsen mound with flanking ditches and large transept chambers, West Kennet was constructed in the middle decades of the 37th century cal BC (Piggott 1962; Bayliss et al. 2007a). Its primary use, which involved the interment of c. 36 individuals by recent estimates, may have lasted less than 50 years (Bayliss et al. 2007a). Following a hiatus of a century or so after the internment of the last of the primary burials, the chambers were progressively filled with a series of secondary deposits of chalk, soil, animal and human bone and pottery. This depositional activity, which could have involved the curation and transport of material from nearby settlement middens, continued on to the latest 3rd or early 2nd millennium cal BC (the bottom end of this range indicated by Late Beaker sherds from the western chamber), by which time access to the chambers had been blocked by the construction of a megalithic façade.

It may be no coincidence that the most elaborate of the region’s long barrows – West and East Kennet and Millbarrow – flank the core of the region where several centuries later the Avebury henge would be constructed, implying that this part of the landscape around the headwaters of the Kennet and the Winterbourne already held especial significance by the middle of the 4th millennium cal BC.

Contemporary with at least some of the long mounds are the earthwork enclosures of Windmill Hill, Rybury and Knap Hill, created on conspicuous hilltops fringing the region. Two kilometres to the north-west of Avebury, that on Windmill Hill is the largest and most elaborate of these sites (Smith 1965b; Whittle et al. 1999), and the only Early Neolithic enclosure to lie within the WHS. In terms of its scale, involvement in extra-regional networks, and the level of participation implied by its construction and use, it may even be regarded as the pre-cursor to the Avebury henge. The enclosure is made up of a series of three concentric interrupted ditches, the outer some 360 m across at its widest point and enclosing an area of 8.5 ha.

The ditches (or at least one of the circuits) on Windmill Hill were noticed by Stukeley (1743) but were not subject to excavation until the 20th century.

H. G. O. Kendall, Vicar of Winterbourne Bassett, collected voraciously on and around the hill during the early 20th century and cut sections across the ditches in the early 1920s. The history of the early investigation of Windmill Hill is fully discussed by Whittle et al. (1999) and Oswald et al. (2001). Smith’s volume Windmill Hill and Avebury (1965b) is the definitive account of the five seasons of excavation undertaken by Keiller between 1925–29, and of the excavations she conducted in 1957–58. Whittle et al. 1999 is also the full report on the 1988 season of excavation at the site and provides a re- evaluation of Keiller’s work. Further discussion and a revised chronological sequence are provided in Whittle et al. 2011 (see also Healy, above). The archive is held largely by the Alexander Keiller Museum, although some finds are on loan to Wiltshire Museum and some were discarded (particularly after a serious fire on Keiller’s property in 1945), dispersed, or lost.

Windmill Hill may have become a focus for periodic gathering and settlement immediately prior to the construction of the enclosure. Excavations in the 1920s uncovered a cluster of over 30 pits in the area later occupied by the inner enclosure; while pits, a hearth and postholes belonging to a substantial structure were revealed under the Outer Bank during investigations in 1957 and 1988 (Smith 1965b; Whittle et al. 1999). The precise chronological relationship between the enclosure, a further cluster of Early Neolithic pits to the south-east excavated in 1993 (Whittle et al. 2000) and a square earthwork likely related to so-called ‘mortuary’ enclosures is uncertain.

Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates from samples recovered from primary ditch contexts shows the Windmill Hill enclosure was created in the 37th century cal BC. The constructional sequence began with the inner ditch, followed most probably by the outer, then middle ditch. The creation of the West Kennet long barrow was probably coeval with the middle part of the sequence (Whittle et al. 2011, 91– 2). The inner and outer circuits currently represent the earliest dated monumental constructions in the region. A late phase of ditch re-cutting and circuit redefinition is seen in the south-eastern part of the outer enclosure, dating to the latest 4th–early 3rd millennium cal BC (see Whittle et al. 2011, 92; and see Healy, above for details). This may relate to the creation of a new approach to the monument from the then busier landscape to the south.

Some of the richest stratified assemblages of earlier Neolithic material culture and faunal remains from Britain have been recovered through excavation at Windmill Hill. They are indicative of periodic large-scale aggregation, feasting and other activities, potentially involving participants from an extensive extra-regional range. Much of this material was deposited in the ditches, often with some formality (Whittle et al. 1999). Fragmentary human remains were also present; often placed alongside the bones of cattle, and perhaps stressing the close relationship people held with their herds and the importance of animals in cycles of feasting and exchange. The range of activities and connections implied by these assemblages represents something of a microcosm of the earlier Neolithic world: gathering, food preparation, feasting, deposition, exchange, marriage and mortuary/ancestor rituals (Whittle et al. 1999).

A single aerial photograph (Major Allen Neg 143) shows a possible cursus monument just outside the WHS to the west, in Cherhill parish (SU 07037000). Close to it are ring ditches, one of which seems to enclose a ring of holes. The site has not been located on the ground, largely due to the disruption to the area caused by the military buildings around Yatesbury (Grinsell 1957, 55).

Possible ‘mortuary’ enclosures have been identified from cropmarks as part of the Folly Hill barrow group near Beckhampton and to the north- east of the East Kennet long barrow (Pollard and Reynolds 2002, 70). An oval parchmark within the NW sector of the Avebury henge (Bewley et al. 1996) bears resemblance to the excavated Middle Neolithic barrow at Radley, Oxfordshire (Bradley 1992); a central pit-like feature perhaps representing a grave. The status of all these sites is yet to be confirmed.

Excavated but anomalous structures include the ditched square earthwork on Windmill Hill (Smith 1965b, 30–3) and the gully-defined enclosure in Longstones Field (Gillings et al. 2008, 21–3). Their dating is not secure, but both may be related to monumentalised ‘halls’ of the early 4th millennium cal BC.

The later 4th and earlier 3rd millennia cal BC may have been a relatively quiet time in terms of monument building within this landscape (Whittle 1993; Whittle et al. 2011), but visits to and deposition at Windmill Hill and several of the region’s long barrows continued, and part of the outer circuit of the Windmill Hill enclosure was re-defined (Pollard 2005; Whittle et al. 2011). It was during the Late Neolithic (c. 2800–2200 cal BC) that the remarkable complex of ceremonial monuments centred on the valley floor was created. The result was a landscape that is equal in scale and complexity to those around Stonehenge, the Boyne Valley of eastern Ireland and Carnac in Brittany. The constructions that make-up the Late Neolithic complex at Avebury include the henge and stone circles, the West Kennet and Beckhampton megalithic avenues, the Longstones enclosure, the Sanctuary, Falkner’s Circle and – occupying the floor of the Kennet Valley – the complex of palisade enclosures at West Kennet and the giant artificial mound of Silbury Hill (Smith 1965b; Whittle 1997a; Gillings et al. 2008). Further afield, there are records of small stone circles at Winterbourne Bassett and perhaps Clatford, while the creation of the Marlborough Mound is now known to have begun during the latest Neolithic (Leary 2011).

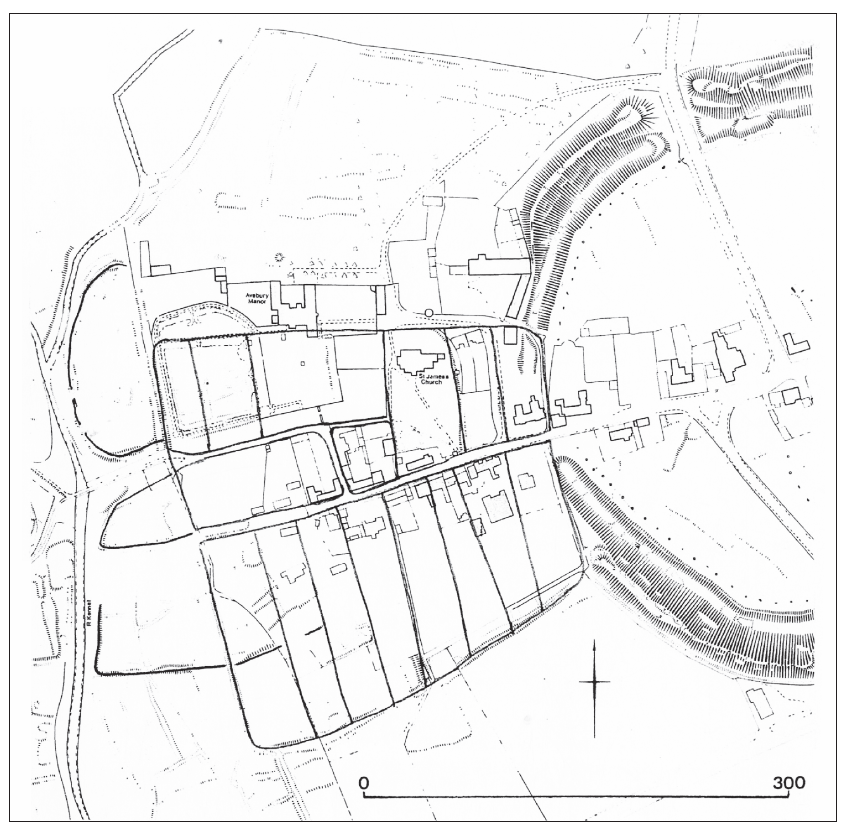

We are now aware that the Avebury henge (Pl. 25) is a complex, multi-phase monument created in a series of stages between the early 3rd and early 2nd millennia cal BC (Gillings and Pollard 2004; Pollard and Cleal 2004). Enclosing a low ridge to the east of the Winterbourne, and overlooked by low hills on most sides, the Avebury henge is defined by a massive earthwork 420 m in diameter, broken by four entrances. Set immediately inside the ditch are the stones of the Outer Circle (the largest stone circle in Europe), themselves enclosing two Inner Circles (Northern and Southern) with complex settings at their centres (the Cove and former Obelisk). Several additional megaliths are scattered along the low ridge running north-south through the henge. Avebury henge can best be conceptualised as a series of nested spaces, the ‘deepest’ and surely most sacred of these being defined by the central settings within the Inner Circles; locations that also offer the greatest visual field of the landscape outside the monument (including views to Silbury Hill and Windmill Hill). The henge earthwork itself is of two phases, the first (Avebury 1) being represented by a smaller bank observed in section in the south-east and south-west quadrants (Pitts and Whittle 1992, 210). The earthwork we see today (Avebury 2) was constructed in the middle of the millennium, probably in the 26th century cal BC (Pollard and Cleal 2004; see Healy, above); and the massive Outer Circle of sarsen stones a little later. The chronology of the other megalithic settings within the henge is poorly understood, although an OSL date for the western stone of the Cove – at 100 tonnes the largest of the stones – indicates it could have been erected as early as 3000 cal BC; while artefactual and radiocarbon evidence shows that megaliths were being erected and re-set within the henge well into the early 2nd millennium cal BC (Smith 1965b; 248; Pollard and Cleal 2004).

The role of the henge is often assumed to have been that of a centre of gathering and worship. In fact very few later Neolithic deposits that might indicate such gatherings have been encountered during excavation: either the monument was kept ‘clean’ or it was visited by only a few (in this sense a ‘reserved’ sacred space within the landscape). By the Early Bronze Age, deposits of human bone were being placed in the henge ditch (Gillings and Pollard 2004, 70–6), suggesting an increasing connection to ancestral rites and perhaps ancestor worship (cf. Parker Pearson and Ramilisonina 1998). While defined as a ‘henge’ and so linked in archaeological categorisation with other later Neolithic-Early Bronze Age ceremonial enclosures, the format of Avebury is unusually elaborate and complex. It has been suggested that the undulating henge banks mimic, as a form of landscape homology, the surrounding downland (Watson 2001): certainly, it is not unusual for monuments to represent aspects of the physical world in microcosm (Bradley 2000). Likewise, individual architectural elements could have served as monumentalised symbolic representations of other structures. The Northern Inner Circle and Cove, for instance, share the format of contemporary ‘square- in-circle’ timber monuments and even the shape of later Neolithic houses.

The henge was not extensively or systematically excavated until the investigations of Gray and Keiller during the 20th century, but there have been a number of smaller excavations over the last two centuries. Finds made prior to Keiller’s work are in general not held by the Alexander Keiller Museum, which was not founded until 1938. Details of the history of investigation can be found in Smith 1965b, Pitts 2000 and Gillings and Pollard 2004.

Reported 1829. Record by Joseph Hunter of digging at the foot of the Cove stones to the depth of a yard or more, but ‘nothing peculiar was observed’ (Long 1857, 326). Hunter was reporting this episode and was not one of those involved.

Reported 1833. Record by Henry Browne of digging at the Cove and finding ‘the place of burnt sacrifices’; probably therefore encountered the burning pit of the northern stone (H. Browne 1833 An illustration of Stonehenge and Abury; information taken from Smith 1965b).

1865. Excavations on behalf of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society by A. C. Smith and W. Cunnington, which lasted for a week. They recognised the burning pit for the northern stone of the Cove and also examined the bases of the surviving stones of the Cove, digging on both west and east sides of the western stone (the ‘back stone’) and close to the southern (side) stone. Apart from the Cove they also trenched through an earthwork in the SE part of the NE quadrant, finding part of a ‘stag’s horn’ and pottery (Smith 1867).

In the SE quadrant they dug a trench at the centre of the Southern Circle, and across it to the north, south-west and east of the centre (each trench c. 60 ft (18.3 m) long). In the centre was a large quantity of burnt sarsen, including fragments and chips, and ‘charred matter’, and there was similar material in all the trenches. The excavators presumed a large central stone in the middle of the Circle but found no evidence of an interior setting to the Circle.

Several trenches were dug into the bank, although locating these is difficult from the report and they do not appear to have been substantial. The largest trench was dug into the bank of the NW quadrant (Pl. 26) and extended ‘many yards’ into the bank; the buried soil proved to be a stiff, red clay. There were no finds from this trench and only one pottery sherd from the smaller trenches (Smith 1867, 209–16).

In total, 14 excavations were undertaken. No human remains were found but finds did include sheep, cattle and horse bones, some of which were clearly modern. Modern glass and pottery was also recovered, but ‘British’ pottery was also found. The buried sites of three stones in the south-western quadrant were also recorded, having been revealed by parching of the grass.

1881. Probing by workmen with iron bars (directed by A. C. Smith and W. C. Lukis) revealed 18 buried stones (16 in the Outer Circle and two in the Northern Inner Circle), half of which were in positions noted by Stukeley as representing stones which had been destroyed. These were uncovered to show the size of the stone, and then re-covered, the sites marked with wooden pegs (Lukis 1882, 153). Lukis found much coarse pottery, and also records the finding of an ‘entire vessel of the same kind of clay’ near to the centre of the Southern Inner Circle when a hole was dug for a flagpole (Lukis 1882, 153).

1894. Excavation carried out for Sir Henry Meux, under the direction of his steward, E. C. Trepplin and supervised in the field by another of his staff, Thomas Leslie. Between the 4 and 19 July a trench was dug through the bank in the SE quadrant, and an extension of 6 ft (1.8 m) was made along the ditch. These investigations were not published, although an account is given in the record of the 50th general meeting of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society (WANHM 33 (1904), 103) and also described by Gray (1935, 103–4). Gray estimated the trench to have been 8 ft (2.4 m) wide by 140 ft (42.7m) long, with a 6 ft (1.8 m) extension along the ditch. Gray describes the excavation from Leslie’s ‘rough diary’, which he possessed. Leslie recorded what ‘appeared to be the grass surface line of an inner rampart, defined by a curved line of vegetable mould 3½ in. in thickness’ (ibid., 104). The turf line beneath the bank was also recognised, reaching a thickness of nearly 2 ft (0.61 m) in the ‘middle of the inner slope’. It appeared to have been burnt, with wood ash visible, and was said to be 2.25 ft (0.69 m) below the level of the adjoining field (1935, 103–4). (A pencil sketch of the bank section, with a report of the dig, probably from Leslie, exists in correspondence with the Cunningtons in the library of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Historical Society, Devizes; information from M. Pitts). There were few finds, all apparently dispersed, although two antler picks were bought by the Wiltshire Archaeological Society at a subsequent sale of Meux’s effects (ibid., 105). Passmore describes three flints as having been found, two of which he illustrates (1935); one is a serrated flake and one a chisel arrowhead, Clark’s type D (Clark 1934). The other object, a combined scraper and point, and the arrowhead, are illustrated by Smith (1965b, 225–6, fig. 76.F188, F189). These three objects were purchased by Passmore, and are in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

1908, 1909, 1911, 1914, 1922. Excavations on behalf of the British Association, directed by Harold St George Gray: mainly in the ditch, but also to reveal one of the stones of the Southern Inner Circle (Gray 1935, 131–2, fig. 5) and three buried stones (or three parts of one stone) within the interior of the Inner Northern Circle (ibid., 108). The excavations were published in 1935. The finds are mainly in Wiltshire Museum, though some were dispersed. A catalogue (compiled by M. Pitts), of the location of antler and bone finds, including dispersed finds, is in the Alexander Keiller Museum. Smith also illustrates and discusses some of the Gray material (1965b, 224, n.1; 228, n.2, 229).

1937, 1938, 1939. Excavations by Alexander Keiller in the NW sector (1937), SW sector (1938) and SE sector (1939). The work was mainly directed at identifying, excavating and restoring the megalithic components of the monument. In the NW and SW sectors the excavations were largely confined to the Outer Circle, while in the SE sector an area in the interior was excavated, including part of the interior of the Southern Inner Circle. A partial section into the bank was undertaken in 1938. Keiller published an interim report on the 1937 and 1938 seasons (Keiller 1939), but the excavations were not fully published until 1965 (Smith 1965b).

1960. Excavations by Stuart Piggott to confirm or refute the existence of a third circle, north of the Northern Inner Circle, and to locate a stone near the northern entrance causeway shown by Stukeley. In neither case did he find evidence for the existence of former stone settings (Piggott 1964).

Post-1960 minor episodes. Since 1960 there have been many minor episodes of archaeological recording, mainly associated with services and maintenance. These have been recorded by staff of the Alexander Keiller Museum (mainly Mrs Vatcher in the 1960s and 1970s; Mike Pitts in the late 1970s and early 1980s), by archaeological contractors and by National Trust archaeologists. Some of these have been reported only in interim, but most of the archives are available in the Alexander Keiller Museum. Excavation preceding work on the north wing of the Great Barn in 1982 was published in full (Evans et al. 1985). National Trust work is recorded by Intervention No.; summaries are sent to the Wiltshire SMR, and full reports and the archive are available at the Alexander Keiller Museum. Work on the backlog of unreported sites from the 1960s onwards is being undertaken by the National Trust at the Alexander Keiller Museum.

1969 Avebury School Site. Unpublished excavation by Mrs Vatcher on the site of the new building for the Avebury Church of England primary school. The area was largely occupied by medieval features, but a small area of remnant bank (surviving to a height of c. 2.0 m) was included in the excavation. Soil profile and molluscs for the remnant bank were published by Evans (1972, 268–74). Finds and the paper archive are in the Alexander Keiller Museum. A reinter- pretation of the buried soils and bank sequence has been published (Pitts and Whittle 1992, 206; and more fully described in Pitts 2000).

2001 and 2002. Work by Oxford Archaeology at the United Reformed Church in advance of the construction of an extension and services revealed a large pit that is probably a stone-hole or stone burial pit of the Southern Inner Circle (Anon. 2003, 229–30).

2003. Excavations were undertaken by the Longstones Project team for the National Trust and English Heritage at the Cove, in advance of the stabilisation of the two remaining stones. The western stone was found to sit in a substantial stone-hole, and was estimated at the time of the work to weigh in the order of 100 tonnes, making it the largest known megalith in the region (Gillings et al. 2008, 166).

Structural relationships place the construction of the Beckhampton and West Kennet Avenues, running from the western and southern entrances of the henge, to c. 2600–2000 cal BC, with a range in the third quarter of the 3rd millennium cal BC being favoured (Gillings et al. 2008). They are, therefore, an addition to, rather than a primary feature of, the Avebury henge. Both are similar in format, comprising for most of their lengths paired settings of sarsen stones. The apparent purpose of the avenues was to physically connect (or to monumentalise existing pathway connections between) the henge and two other monumental constructions: the Longstones enclosure at Beckhampton and the Sanctuary on Overton Hill. Along their lengths they take in locations that had earlier witnessed occupation, such as the midden spread at the base of Waden Hill (Smith 1965b).

The West Kennet Avenue (Pl. 27) links the henge to the Sanctuary, some 2.3 km to the south-east. For the purposes of this discussion, the avenue will be split into three areas:

Area 1. The northern third of the avenue was excavated and reconstructed by Keiller in 1934–5 and 1939; two stone-holes within this length had earlier been excavated by M. E. Cunnington in 1912. Keiller ‘stone-hopped’, and so large parts of theinterior of the Avenue in this area have not been investigated archaeologically.

Area 2. The rest of the avenue between areas 1 and 3 has only been partially investigated. The area from just to the south of the Middle/Late Neolithic ‘Occupation Site’ excavated by Keiller to a farm track north of the A4 was investigated by geophysical survey (published in Ucko et al. 1991). The part of the West Kennet Avenue south of Keiller’s excavated area and west of the lane from the A4 to Avebury (which includes the area geophysically surveyed) was intensively fieldwalked in 1995. A Ground Penetrating Radar survey has been carried out on the avenue south of the length excavated by Keiller. This has successfully identified a number of buried stones (Shell and Pierce 1999). Two stones survive in this area, and the position of a third was located to the north of the A4 by the Ordnance Survey in 1883 (see David, above).

Area 3. At the southern part of the avenue, where it straddles the A4 to the east of West Kennett House, five stone-holes have been excavated (see Smith 1965b, fig. 72) and four stones survive in the hedgerow bordering the A4. The very southern end of the avenue where it joins the Sanctuary was excavated by Cunnington in 1930. The far eastern part of the Avenue as it approaches/leads from the Sanctuary was fieldwalked in 1991 by the National Trust.

A short section of the avenue north of New Cottages was examined through excavation in 2002– 3 (Gillings et al. 2008, 133–7). No trace of stone-holes was found, although a sarsen thought to have been part of the avenue and buried in 1921–2 to afford it protection was located. Here the structure of the avenue appears to deviate from its normal pattern of paired stones, perhaps becoming discontinuous or being reduced to a single line of more widely spaced megaliths. It may be significant that this is the section of avenue closest to the West Kennet palisade enclosures.

The existence or non-existence of an avenue of standing stones running towards Beckhampton and connected in some fashion with the two standing Longstones was a matter of debate from the early 18th century when its presence was postulated by Stukeley until 1999 when its existence, at least in Longstones Field, was demonstrated (Gillings et al. 2008). Ucko et al. (1991, 195) note that from 1719 to 1723 Stukeley did not recognise any entrance to the henge as original other than the southern one, so that the question of an avenue to the west did not arise. None of the previous observations by other writers had noticed such a setting of stones.

In Abury, Stukeley describes the course of the Avenue in some detail (1743, 34–7; tab VIII), charting its course from the western entrance to the henge, along the village street, across the Winterbourne, out past South Street to the Longstones where one of the stones formed the back of a Cove, down to Beckhampton and beyond, finally terminating below Cherhill and Oldbury Downs. The descriptions seem fairly confident at the village end, becoming vaguer as the avenue passes westward, until the final western stretch beyond the Longstones was clearly no more than wishful thinking given spurious support by the occurrence here of natural sarsens (Gillings et al. 2008, 109–19). The avenue appears to describe a gentle arc running from the western entrance of the henge to the Longstones near Beckhampton, traversing a distance of 1.3 km and crossing the Winterbourne stream.

As with the West Kennet Avenue, discussion of the course of the Beckhampton Avenue is best approached through its division into three areas:

Area 1. The course and format of the avenue along the 270 m length of the High Street – of paired stones, perhaps reducing in longitudinal and transverse interval as it approaches the western entrance of the henge – has been reconstructed through synthesis of antiquarian and more recent observation (Gillings et al. 2008, 117–18). A number of toppled stones may still lie buried.

Area 2. Little is known of the course or morphology of the avenue in its length from the western end of the High Street to the eastern edge of Longstones Field, in part due to the presence of farm buildings within this area. Geophysical survey by Jim Gunter and Vaughan Roberts within Manor Farm Paddock did identify a series of anomalies that could well relate to the avenue, but which might suggest a more complex arrangement of stones than the typical paired settings (Gillings et al. 2008, 115).

Area 3. Subjected to geophysical survey by English Heritage in 1989, 1999 and 2000, and by the Longstones Project in 2003, selected sections of the avenue were excavated in 1999, 2000 and 2003 (Gillings et al. 2008, 62–108). This work showed the avenue to terminate just to the south-west of the former footprint of the Longstones enclosure; its first phase comprising a T-shaped setting of stones, subsequently modified to create the Longstones Cove. Large quantities of worked flint were found in association with the terminal settings (Gillings et al. 2008).

The larger stone of the Longstones Cove (Adam) fell in December 1911 and was re-erected by Mrs Cunnington in 1912 (Cunnington 1913) (the stone was not re-erected in quite the same attitude as before its fall). During the excavation of the stone- hole and the area around it a disturbed burial was found, associated with sherds of a Northern/Middle Rhine Beaker.

By contrast with the valley floor setting of many of the Late Neolithic monuments, the multiple timber and stone circles of the Sanctuary (Pl. 28) occupy an unusual location on the end of Overton Hill (albeit one with vistas over the river and West Kennet palisade enclosures). This was a locale with a long prior history of activity, judging by the residual sherds of Early Neolithic bowl pottery and Peterborough Ware discovered during the original excavations (Cunnington 1931). Perhaps, as with the Avebury henge, it was the deep historical significance of this place that made it an appropriate location to construct a key monument. On the basis of analogy with other Late Neolithic multiple timber circles, associated artefactual evidence (Grooved Ware and chisel arrowheads) and structural relationships, the timber settings of the Sanctuary can be placed in the middle of the 3rd millennium cal BC (Pollard 1992).

Excavated by M. E. Cunnington in 1930, the Sanctuary was initially interpreted as an unroofed timber structure that was later replaced by a stone structure. The surviving stones were destroyed in 1724. The site was not totally excavated: large areas between the outer stone circle and the outer posthole circle were left unexcavated, as was the vast majority of the area immediately outside the structure (Cunnington 1931, pl.1). Various re-interpretations of the site have been proposed. R. H. Cunnington (see M. E. Cunnington 1931) attempted to place all the postholes as components of a single roofed building. Piggott (1940) regarded the site as a succession of progressively larger roofed timber buildings, the last with a stone circle incorporated in the structure alongside wooden posts. He considered that the outer stone ring was added as a fourth phase. Pollard (1992) rejected the more complicated phasing for a single or at most double phased (one timber and one stone) monument. The majority of the finds from The Sanctuary are in Wiltshire Museum; the animal bone is in the Natural History Museum. In 1999 a limited area, within the area excavated by Mrs Cunnington, was reopened by Mike Pitts. His work showed evidence of multiple and probably rapid episodes of post replacement in some instances, which would be incompatible with interpretations of the timber settings as a roofed structure (Pitts 2001). The process of post replacement could be linked to short ‘ritual cycles’ of construction and dismantling. With deposits of Grooved Ware, animal bone and lithics associated with its timber phase, activities at the Sanctuary were broadly analogous to those undertaken at the settings inside the West Kennet palisade enclosures. The conversion to a stone monument probably occurred in the third quarter of the 3rd millennium cal BC, when the monument was connected to the Avebury henge via the south-east terminal of the West Kennet Avenue.

Close to the Sanctuary human bones were discovered in the 17th century by a Dr Toope of Marlborough, who corresponded with John Aubrey (letter of 1 December 1685; quoted in Long 1857, 327). Dr Toope reported having encountered workmen who had been making new boundaries to enclose land for grass, who had found bones. Dr Toope returned and collected ‘bushells’ for making into medicine. The burials were shallow, only a foot or so beneath the topsoil, and Toope reported their feet as lying towards the ‘temple’ (the Sanctuary). ‘I really believe’ he wrote, ‘the whole plaine, on that even ground, is full of dead bodies’. The impression given, although the point is not made specifically by Toope, is that the burials were extended rather than crouched, and therefore perhaps less likely to be Neolithic or Bronze Age than later. If the burials were on the level ground to the north they must have lain very close to the Roman road and might therefore be Roman. There are both Roman and (early) Saxon burials within the Overton Hill barrow cemetery, on the edge of which the Sanctuary is situated.

First recognised as a cropmark on an aerial photograph taken by English Heritage in 1997, the Longstones enclosure is traversed by the later line of the Beckhampton Avenue. The enclosure was excavated by the Longstones Project in 1999 and 2000 (Gillings et al. 2008, 9–52). It comprises a flattened oval circuit defined by a shallow ditch, 140 x 110 m across, with a 45 m-wide entrance gap on its eastern side. A small quantity of worked flint, animal bone and Grooved Ware was recovered from the base and lower fills of the ditch. Radiocarbon dates place its construction most likely in the range 2660–2460 cal BC (see Healy, above). The ditch was backfilled apparently prior to the construction of the avenue. The enclosure’s morphology is unusual, sharing more similarities with earlier Neolithic formats than contemporary henge monuments.

This circle, c. 250 m east of the West Kennet Avenue, was observed by a Mr. Falkner in 1840, who saw one standing stone, two recumbent stones and nine ‘hollow places’ where stones had stood. The circle was recorded as c. 36 m in diameter (Long 1857). Only the standing stone now remains. Excavations in 2002 identified stone-holes and stone destruction pits relating to some of the missing megaliths. The work also demonstrated that Falkner’s Circle was, like the circles inside the henge, a megalithic construction from the outset (Gillings et al. 2008). Associated with a small amount of Grooved Ware and later Neolithic worked flint, its chronology is only loosely defined.

Set in the dry valley to the south of Avebury, and ‘ignored’ by the course of the West Kennet Avenue, the location of this monument is an interesting one. It lies at the southern end of an extensive former spread of sarsen stone, seemingly at the point where the large ‘grey wethers’ – similar to those employed in the Avebury settings – diminished in number and smaller blocks of reddish-brown sarsen became more prevalent.

Other small stone circles are noted in the antiquarian literature and lie outside the area of the WHS. That at Winterbourne Bassett, 5 km to the north of Avebury, was first recorded by Stukeley, who described a monument comprising two concentric rings of stone with a single stone located to the west. Its true location (not that traditionally ascribed: Smith 1885, 76–8) was re-established through surface survey and excavation by Jim Gunter in 2004.

The Broadstones or Clatford circle was first recorded by Aubrey as comprising eight recumbent stones ‘In a Lane from Kynet towards Marlborough’ (Aubrey 1980; Meyrick 1955; Burl 1976). Stukeley added the observation that four other stones may have formed the beginning of an avenue running out from the circle, but also entertained the possibility that the sarsens, apparently roughly shaped, were destined for Stonehenge. Its former position has been hypothesised (in 2011) as lying immediately west of Barrow Farm, just north of the A4, in close proximity to the Manton Barrow (Preshute G1: Cunnington 1907). The possibility that the stones represented megaliths in transit to Stonehenge rather than a dilapidated stone circle is currently being investigated by the ‘Stones of Stonehenge Project’ (M. Parker Pearson pers. comm.).

The claimed stone circle at Langdean (Passmore 1923) could be a barrow kerb (Barnatt 1989, 505: see Mortimer 1997 for further review); while that recorded by Stukeley south of Silbury near Beckhampton Penning (1743, 46) and later investigated by Smith (1878; 1881) may be the site of an enclosure or denuded long barrow (Barnatt 1989, 505; Barker 1985, 24; Mortimer 1998).

Two substantial Late Neolithic palisade enclosures and associated features are situated in the valley of the Kennet to the east of Silbury Hill. Their presence was first determined by an aerial photograph taken in 1950 and observations made during pipe-laying work in the early 1970s. Excavations directed by Alasdair Whittle in 1987, 1989, 1990 and 1992 elucidated their form, demonstrated their date, identified a range of structural components, and produced large assemblages of Grooved Ware, animal bone and worked flint (Whittle 1997a). The eastern of the two enclosures (Enclosure 1) comprises two concentric circuits of palisade, enclosing approximately 4.2 ha and straddling the River Kennet. The single circuit of Enclosure 2 is located just to the south of the river and immediately west of Enclosure 1. It defines an area of approximately 5.5 ha within the eastern third of which are at least three ditched and timber circles. A large area within the western portion of the enclosure looks, on current evidence, to be empty of structures. Radial palisade lines run from Enclosure 2 to the south, connecting with further circular/sub- circular enclosures.

The scale of these constructions is evident from Whittle’s estimate that 40,000 m3 of mature timber were required for their construction (Whittle 1997a, 154), much perhaps brought from secondary oak woodland on adjacent downland. Lengths of palisade line may have been subject to intentional burning. While defence may have been a feature, the large quantities of Grooved Ware and the pig-dominated faunal assemblage show a major role for these enclosures as the location for gathering and feasting. Their precise chronology and sequence of construction remains to be established, but a cautious reading of available radiocarbon dates suggests a range of 2340–2130 cal BC (see Healy, above), and so broadly contemporary with the construction of Silbury Hill and perhaps the West Kennet and Beckhampton Avenues.

Subsequent transcription of aerial photographs has shown the complex of palisades to be more extensive than initially thought; extending to the south along the bottom of the dry valley perpendicular to the Kennet (Barber 2013; Crutchley 2005). This work has also identified a second small timber circle within the palisade circuits of Enclosure 1. Surface collection by Wessex Archaeology over part of Enclosure 2 and to the south identified localised, low-density concentrations of worked and burnt flint, along with a massive Late Neolithic core (Pl. 29) (P. Harding pers. comm.).

The West Kennet palisade enclosures lie within the shadow of the monumental mound of Silbury Hill (Pl. 30), the largest prehistoric artificial mound in Europe. Silbury Hill has long attracted speculation about its age and function. Several episodes of intrusive investigation have taken place on and around the hill since Edward Drax first sank a central shaft from the top of the mound down to ground level in 1776. In 1849 a horizontal tunnel terminated in galleries excavated in search of a central burial, as in 1922 when exploratory trenches were dug opposite the eastern causeway. In 1867 excavations proved that the Roman road (the present-day A4) swerved around the base of the hill, and therefore post-dated it. In 1886 the ditch around the hill was explored by sinking 10 shafts into it (Whittle 1997a, 10). Three seasons of excavations were carried out by Professor R. J. C. Atkinson in 1968–70. Atkinson identified three phases of construction of the hill, and important environmental information was recovered (Atkinson 1967; 1970). These excavations were fully published by Whittle (1997a).

A programme of re-dating suggested that the primary mound of Silbury was constructed in the third quarter of the 3rd millennium cal BC (the 24th or 23rd centuries), with completion either relatively swift or taking until the end of that millennium (Bayliss et al. 2007b). Further dates on material from a recent programme of excavation and recording, undertaken in advance of consolidation work (Leary and Field 2010), have produced a revised model which suggests a start at 2490–2450 cal BC, and a time span of 50–150 years for construction (Leary et al. 2013b). That work also highlighted the complexity of the constructional sequence, beginning with a succession of small gravel and organic mounds, the space they occupied then perhaps defined by a large ditched enclosure, in turn covered by several phases of chalk mound resulting in the structure seen today (Leary et al. 2013b). The significance of Silbury may lie in its marking the source of the Kennet. Not only is the mound sited on a low chalk spur jutting into the valley floor close to the Swallowhead springs, but river clay and gravel were used in quantity in the initial mound phases.

Downstream from Silbury Hill and the West Kennet palisade enclosures, in the zone between the eastern boundary of the WHS and Marlborough, are further monuments of known or suspected Neolithic date. Moving from west to east, the round barrow West Overton G19 began as a simple ring-ditch constructed in the early part of the 3rd millennium cal BC (Anon. 1988; see Healy, above). The Broadstones or Clatford circle has been described above. Geophysical survey by the Stones of Stonehenge Project in 2011 revealed a possible small henge monument adjacent to the Manton (Preshute G1a) barrow. A recent programme of coring at the Marlborough Mound – long suspected to be a potential Late Neolithic monumental mound analogous to Silbury Hill – has shown it to have been constructed in a series of stages within the second half of the 3rd millennium cal BC (Leary 2011).

The Avebury henge, avenues and the Sanctuary continued to attract attention into the Early Bronze Age (latest 3rd–early 2nd millennia cal BC), as evidenced by deposits of pottery and other materials, and burials of single individuals against standing stones (eg, stones 22b, 25a, 25b and 29a of the West Kennet Avenue: Smith 1965b, 229–30). However, during the course of the Early Bronze Age emphasis gradually shifted away from the Late Neolithic complex. The distribution of Beaker pottery and associated flintwork and burials in the region is much more extensive than that of later Neolithic activity (Zienkiewicz and Hamilton 1999, 307), and highlights a ‘re-colonization’ of the high down around the head of the Kennet Valley. Evidence of cultivation also increases (Pollard and Reynolds 2002, 136–7).

The most visible statement of change comes in the form of extensive round barrow cemeteries, established during the course of the Early Bronze Age. There are over 300 known round barrows within the region, around half of which lie within the WHS. Barrow cemeteries, ploughed and extant, occur on Overton Hill/Down (West and Severn Barrows), Waden Hill North, Windmill Hill, Folly Hill, Fox Covert, Beckhampton Penning and west of North Farm, West Overton (Soffe 1993; Cleal 2005). Their distribution shows a loose clustering around the henge and the Sanctuary (ibid., 121). A number of those on Windmill Hill and Overton and Avebury Downs were the focus of recorded antiquarian investigation by Merewether (1851) and Thurnam (1860; 1871). Grinsell (1957) remains a useful and accessible summary of barrow investigations prior to the mid-1950s; while Cleal (2005) provides a full and detailed review of the evidence and considers the siting of barrow cemeteries in relation to existing monuments and topographic features.

None of the primary grave assemblages encountered (both inhumation and cremation being recorded rites) are particularly rich, or particularly early (Cleal 2005). Few of the round barrows within the region have been the subject of extensive modern excavation. Within the area, full investigation of West Overton G6b during the 1960s revealed a primary inhumation with Beaker and ‘leather working’ kit, and a series of secondary/satellite inhumation and cremation burials (Smith and Simpson 1966). The barrow itself was unusual in comprising a low, unditched mound encasing an annular flint and stone bank. Limited excavation in advance of pipeline renewal of the ‘Stukeley’ barrow on the southern slope of Waden Hill did not reveal any funerary deposits (Powell et al. 1996).

A radiocarbon date of 2020–1770 cal BC (at 95% probability) has recently been obtained for the primary burial under West Overton G1, just to the east of the Sanctuary. Accompanied by a bronze flat axe head, crutch-headed pin and tanged knife, this is the first burial of the Wessex 1 series to be scientifically dated (Needham et al. 2010a).

As Beaker-associated burials against standing stones indicate, not all graves of this period were marked by barrow mounds. Flat grave cemeteries are recorded on Overton Hill (Fowler 2000a, 82–6), where three inhumations were encountered during the excavation of an Iron Age settlement, and immediately north of Windmill Hill in Winterbourne Monkton parish (Grinsell 1957, 126). Over 30 burials were discovered here at various times during the 19th century. Nearly all were in circular pits or graves covered with large sarsen slabs, one also being paved with stones. The burials included infants and adults, both male and female, generally without grave goods. The chronological span of these remains to be established, although some are certainly Neolithic (see Healy, above). One was associated with two Beakers, a greenstone pebble, a flint knife, jet buttons and a ring (Smith 1885, 85–6; Annable and Simpson 1964, 39). Single and apparently isolated sarsen- capped Beaker burials are known from the area of Beckhampton (Young 1950; Grinsell 1957, 34).

by Clive Ruggles