This volume represents the result of several years of work to produce an Archaeological Research Assessment and Research Agenda for the West Midlands region, which embraces the counties of Herefordshire, Staffordshire, Shropshire, Warwickshire, Worcestershire and the former West Midlands County. This large region covers a disparate landscape from the southern edge of the Peak District in the north, to the Welsh border region to the west, and a major industrial conurbation in the centre, surrounded by a rich archaeological and historical agricultural landscape.

Despite this disparate landscape the region has a strong tradition of informal liaison within its diverse archaeological ‘community’. This includes County Archaeologists and other Local Authority Archaeological Officers, Sites and Monuments Record (and Historic Environment Record) Officers, cathedral and diocese archaeologists, academics, contracting units and consultants, independent archaeologists, professionals and non- professionals, all of whom make an active contribution to the archaeology of the region. There is also a number of representative groupings, including the West Midlands Regional Group of the Council for British Archaeology (CBA WM), the West Midlands Group of the Institute for Archaeologists (IfA WM), the West Midlands regional office of English Heritage, the West Midlands Archaeological Collections Research Units (WEMACRU), and the Association of Local Government Archaeologists (ALGAO).

It was these existing links and lines of communication that were critical in the success of the research framework process, ensuring a high attendance and level of engagement at the Research Assessment seminars and a diverse wealth of knowledge and experience to draw upon in the preparation of this volume.

The overall aim of the Research Framework process was to produce an archaeological research framework for the region (including the proper integration of artefactual and ecofactual interests) that will provide a viable, realistic and effective academic basis for undertaking archaeological intervention, either as the result of development-related operations or to underpin future research designs. The outcome will enable curators to integrate appropriate research strategies within their specifications, and ensure that contractors tender and operate in full awareness of local designs. Equally, it will inform museum curators, education officers and university staff and students with regard to the research parameters of the region.

The starting point was the Department of the Environment’s Planning Policy Guidance No 16 (DoE 1990), dealing with archaeology and planning, which emphasised the need for proper research frameworks within which archaeological work might be located, and raised issues that were explored further in the English Heritage survey Frameworks For Our Past (Olivier 1996). Here, it was further argued that the public perception of archaeology and the need for acceptable public accountability ‘make it essential that the discipline acquires a proper means of selecting and targeting local and regional priorities in order to justify curatorial policies and decisions’ (ibid, 2). The context for dealing with planning issues should be clearly and explicitly informed by the needs of archaeological research.

In the West Midlands, subsequent English Heritage guidance, through two public meetings (in June and September 2000), underlined the necessity of producing a regional research framework not only as a ‘flexible research tool’, but also one which would serve to maintain a necessary academic basis to developer-related archaeology.

A working party (or steering group) was selected and confirmed through the two public meetings and through consultation within the interested parties represented.

This group (which became the project’s Management Committee) reflected the wider forum of archaeological interest and expertise within the region, and drew its membership from English Heritage, the SMRs, ALGAO, contracting units and consultants, Higher Education, CBA WM, the IfA WM, museums, archaeological sciences, artefactual specialists and independent archaeologists. The group was tasked with producing an outline framework, and with providing an information cascade mechanism. Its proposals were reported and validated in a further public meeting (in March 2001) representing the diverse archaeological interests within the region.

The need to develop a research framework has long been acknowledged within the region. Local authority archaeological services have been actively engaged in producing their own strategic plans, and representative groups such as WEMACRU, ALGAO and the IfA have also engaged with the process. Even before PPG 16 and Frameworks For Our Past highlighted these issues, specialist groups were attempting to address the need for coherent research approaches. The CBA WM has also produced a research plan, with its own membership in mind (1999, 2-10).

At the time the process was initiated in the West Midlands, research frameworks had already been produced (or were in production) for the East Midlands, the Eastern Counties, and the Greater Thames Estuary among others. West Midlands archaeologists have therefore enjoyed the considerable benefit of having been able to review the approaches to this process adopted in other regions and, thus informed, to consider the particular needs and characteristics of their own region.

The Research Agenda for the West Midlands is the result of a two-stage process:

Although not originally anticipated to form part of the work undertaken for the Resource Audit, the major part of this stage of the project involved the collation and amalgamation of data from all of the County and City Sites and Monuments Records (now for the most part Historic Environment Records) across the region (11 separate databases in all) in order to produce period-based distribution maps of recorded sites and findspots for the entire region using GIS software, something which had not been attempted previously. These maps form the basis for the distribution maps contained throughout this volume. The production of the maps was supported by other information, including the compilation of bibliographies (including grey literature), and a summary audit of museum collections.

There were various problems of incompatibility between the different SMR databases (for instance, the names of site and find types differed between databases, as did the level of subdivision within periods, many databases also using the ‘catch-all’ period ‘prehistoric’, and there was inconsistent recording of artefacts, something which will be addressed in the future (see Chapter 9)). It was thus a labour-intensive and time-consuming piece of work but it was considered that the end justified the means and that the results of this exercise were worthwhile, particularly for the pre-medieval periods.

Despite the various biases and other problems, the HERs represent the most important source of archaeological data for the region, and the distribution maps also served the purpose of identifying where problems were in terms of compatibility across the region. The datasets that were used to prepare the maps were current in early 2001 (with the caveat that there were data-entry backlogs across the region ranging from a few weeks to an estimated four years) but have been updated when appropriate for the production of the maps in this volume.

The Research Assessment stage of the project comprised seven period-based seminars (with the period divisions drawn as per the separate chapters of this volume) held between June 2002 and June 2003. Over 25% of the seminar papers were written and delivered by ALGAO/SMR Officers. Another 25% were undertaken by Contracting Units or Consultancies. The rest were undertaken by academics, independent parties and English Heritage officers. It was intended to make the scope of the seminars broad in order to include as many participants as possible and, in order to facilitate constructive comparison across the region, each paper was prepared to a brief, which included the following elements:

The seminars were held at different venues across the region and saw an average attendance of c 65 people (with the largest number of people, 81, attending the Roman period seminar). Between 13 and 16 papers were presented at each day-long seminar: the first half of each seminar consisted primarily of county-based papers, with the afternoon generally consisting of thematic papers followed in most cases by a national overview given by an invited speaker from outside the region. Time for discussion was programmed in throughout and at the end of the day.

The papers presented at each seminar were then posted in draft on the project’s website: (http://www.iaa.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/wmrrfa/index.shtml),where they remain. This was in order to invite comments from all interested parties, which could then be incorporated into the papers where appropriate. The revised papers were then collated and circulated to the authors of the chapters in this volume as an essential basis for the production of the period-based chapters.

A subsequent series of seven smaller period-based discussion groups were held between July 2003 and June 2004, focusing on the Research Assessment papers. These were held at the University of Birmingham and were chaired by the respective future authors of the chapters of this volume. The object of these meetings was to focus the contributions from the general meeting, define a draft list of research topics, and generate cross-period themes. The chapter authors then embarked upon writing the Research Assessment/ Research Agenda chapters, for which they drew on the papers presented at the Research Assessment and the discussions (which were recorded) at the Research Agenda meetings. Chapters 8, 9 and 10 of this volume were originally circulated by e-mail to those on the project’s extensive mailing lists for comment.

It was of course recognised that the county-based and thematic papers presented at the Research Assessment seminars formed a useful resource in their own right and, as well as publishing the draft versions of these on the web, another early outcome of the research framework was the idea for a new series of volumes entitled The Making of the West Midlands, the first volume of which, on the early prehistory of the region, has now been published (Garwood 2007); the series is to comprise the full papers presented at each research framework seminar in a series of period-based volumes.

This separate series of volumes is an added bonus to come out of the framework process, will ‘plug’ a large gap in the current availability of texts on the archaeology of all periods in the West Midlands, and will represent a landmark series in the drawing together and publication of the archaeological evidence for this region.

From discussions held at the Research Agenda meetings, it became clear that there was a desire to maintain the informal networks of people who had been brought together by the research framework process. For example, it was suggested for some periods that interested parties continue to meet at organised seminars held at regular intervals in order to maintain the momentum that the research framework process has started. A related material outcome of this, for instance, was the establishment of the West Midlands Palaeolithic Network (or Shotton project).

The maintenance of such networks would be a very positive outcome for the region which has been born out of the Research Framework process.

The unintended delay between the initial preparation of the chapters forming this volume and their publication means that, despite some revisions in the interim, the contents of the published volume make no reference to recent significant events, two of which in particular should be mentioned here.

First is the much-publicised discovery of the ‘Staffordshire Hoard’ in a field near Lichfield in July 2009, an Anglo-Saxon hoard comprising more thatn 1500 (mostly military-related) items of gold and silver. The implications for the West Midlands region of this nationally significant find will be addressed in the Early Medieval volume of the The Making of the West Midlands series referred to above (edited by Della Hooke).

Second, the replacement of planning Policy Guidance notes 15 and 16 with the new Planning Policy Statement 5 (PPS5) in March 2010, and the implications this has for the management of the historic environment within the region, should also be noted.

This Framework was originally published by the University of Birmingham and Oxbow Books in 2011, and is now presented online in it’s original text (December 2021).

The publication of this volume marks the culmination of several years of coordinated research, seminar presentations and the personal contribution of many individuals; it also represents a major step forward in the future management of our archaeological heritage in the West Midlands. This was a project started in 2001 with a series of open meetings in the region, drawing together archaeologists from local societies, universities, local authorities and field units as well as interested individuals both professional and amateur. The initiative and the funding belonged to English Heritage and the purpose was to provide a research framework for the region in order to ensure that future archaeological work, the majority of which was developer-led, might be better aligned to research purpose and to the resolution of academic goals.

The committee that evolved from these open meetings took upon itself to identify appropriate chronological periods for study and gathered information from local museums and collections, sites and monuments records/historic environment records, excavation reports published and unpublished, artefact specialists and experts in a host of subject areas ranging from geology to place-names. This data was then drawn together and presented in a series of period seminars, discussed, synthesised, and finally published in this volume. Although ostensibly a simple process, it involved many individuals working in their own time, fitting in the research around other commitments, and collaborating with individuals with other areas of interest. It was a process that additionally served to bring together the various components of a sometimes fragmented archaeological community. It is a great credit to the enthusiasm and energies of the coordinator Sarah Watt, and to the patience of the English Heritage representative Ian George, that the work has been completed so superbly.

The results of this work have provided us with an audit: it has defined our strengths and weaknesses, in some cases quite frighteningly; it has shown where the gaps in our knowledge lie both geographically and chronologically, and it has demonstrated where we may need to exert greater research effort. This is a volume which we hope will find many homes throughout the region and will be used to underpin the research designs and commercial specifications of archaeology throughout the next decade and beyond. The editor, the contributors and the many individuals whose efforts underpinned the papers here are to be congratulated on setting the archaeology of the West Midlands on a new footing.

John Hunter

Professor of Ancient History and Archaeology University of Birmingham

The organisation and production of the Research Framework has relied on the support and hard work of a wide range of individuals and organisations. As well as the authors of the chapters in this volume, who have done a superb job of assimilating an enormous amount of data and supplementing it with their own research and knowledge, I would like to thank all those who participated in the process, especially the authors of the county resource assessment papers and themed regional papers presented at the series of Resource Assessment seminars held in 2002-2003. These included local authority and university archaeologists as well as independent archaeological practitioners, who took on the task of auditing the region’s archaeology:

Andy Boucher of Archaeological Investigations Ltd.; Mike Hodder of Birmingham City Council; Paul Garwood, John Halsted, Della Hooke, Alex Jones, Roger White and Ann Woodward of the University of Birmingham, and Simon Buteux, Sally Crawford, Jane Evans, Iain Ferris, James Greig, Annette Hancocks, John Hunt and Alex Lang formerly of the University of Birmingham; Peter Guest of Cardiff University; Iain Soden formerly of Coventry City Council; Nathan Pittam of Coventry University; Andy Myers of Derbyshire County Council; Pete Boland and John Hemingway of Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council; Martyn Barber, Mark Bowden, Paul Stamper and Chris Welch of English Heritage; Julian Cotton, Tim Hoverd and Keith Ray of Herefordshire County Council, and Paul White and Rebecca Roseff formerly of Herefordshire County Council; Paul Belford of Nexus Heritage; Richard MacPhail of University College London; Jeremy Milln of the National Trust; Gavin Kinsley of Nottingham University; Paul Booth of Oxford Archaeology; Mike Watson and Andy Wigley of Shropshire County Council; Chris Wardle and Bill Klemperer formerly of Staffordshire County Council; David Barker formerly of Stoke-on-Trent City Council; David Jordan of Terra Nova Ltd.; Nicholas Palmer, Stuart Palmer and Jonathan Parkhouse of Warwickshire County Council; Stephen Hill formerly of Warwick University; Angie Bolton of the West Midlands Portable Antiquities Scheme; Mike Shaw of Wolverhampton City Council; James Dinn of Worcester City Council; Malcolm Atkin, Victoria Bryant, Hal Dalwood, Derek Hurst, Robin Jackson and Liz Pearson of Worcestershire County Council, and Neil Lockett formerly of Worcestershire County Council; Nigel Baker; Hilary Cool; Bob Meeson; Stephanie Rátkai; Barrie Trinder; Alan Vince; John van Laun. Lawrence Barfield of the University of Birmingham, who sadly died in July 2009, also made a significant contribution.

Thanks also to all the delegates who attended the seminars and contributed to the discussions, particularly the invited chairs and discussants (all included above) and those invited to fulfil the daunting task of summarising each seminar, setting the West Midlands in its wider national context: John Hines and Niall Sharples of Cardiff University, Glyn Coppack of English Heritage, Jeremy Taylor and Marilyn Palmer of the University of Leicester, and Richard Bradley of the University of Reading.

English Heritage has generously funded the project and special thanks go to their representative Ian George for his help and support throughout. Thanks also to John Hunter for his overall management of the project and to Caroline Sturdy for her support in the final stages of coordination for publication and for collating the illustrations. Henry Buglass of the Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity, University of Birmingham, produced the original distribution map template used throughout this volume and all the

distribution map figures, and prepared the illustrations for publication. The distribution maps are based on data collated from all the region’s Sites and Monuments Records at the beginning of the project; thanks to all the SMR and HER officers who supplied this information and to all the local authority archaeologists who took the time to meet me and talk about the archaeology of their respective areas.

Thanks are also due to the members of the project’s Management Committee for their invaluable support and assistance (and good ideas). The committee consisted of: Andy Boucher, Victoria Bryant, Vince Gaffney, Ian George, Mike Hodder, Della Hooke, John Hunt, John Hunter, Lisa Moffett, Cathy Patrick, Stephanie Rátkai, Mike Shaw and Mike Stokes. Mike Stokes, who died in February 2005, is sadly missed.

Sarah Watt

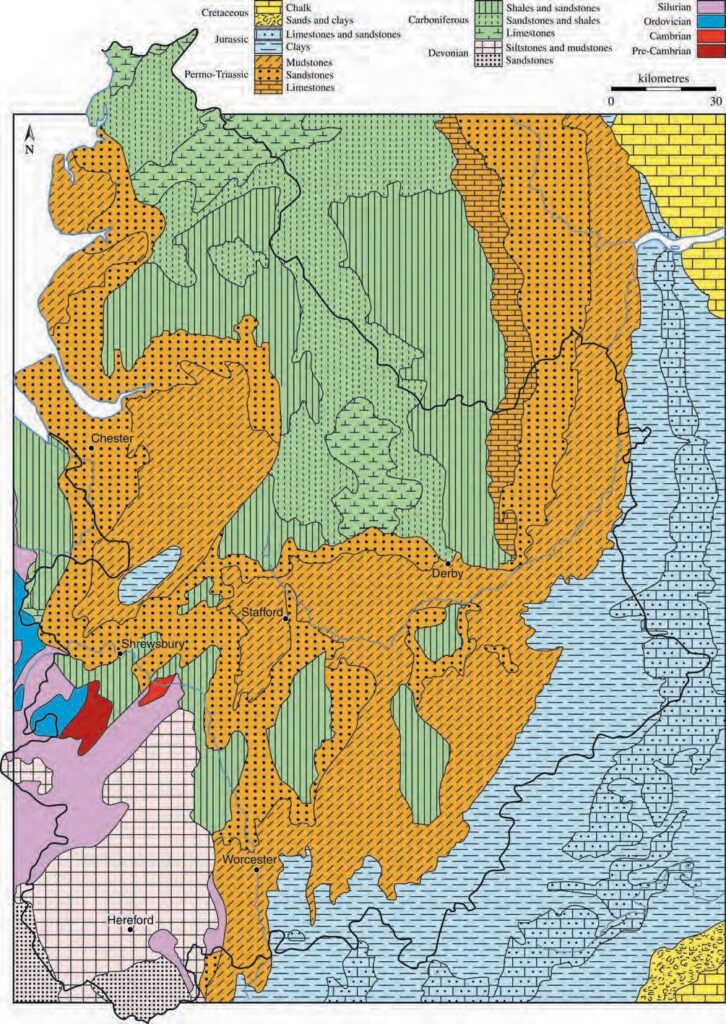

The West Midlands is taken to cover the West Midlands metropolitan area and the counties of Herefordshire, Shropshire, Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire. Covering a large part of central England and the Welsh Borderlands, this area incorporates a variety of ‘solid’ geological formations that range in age from late Precambrian to Jurassic (British Geological Survey, 2001; Fig 1.1).

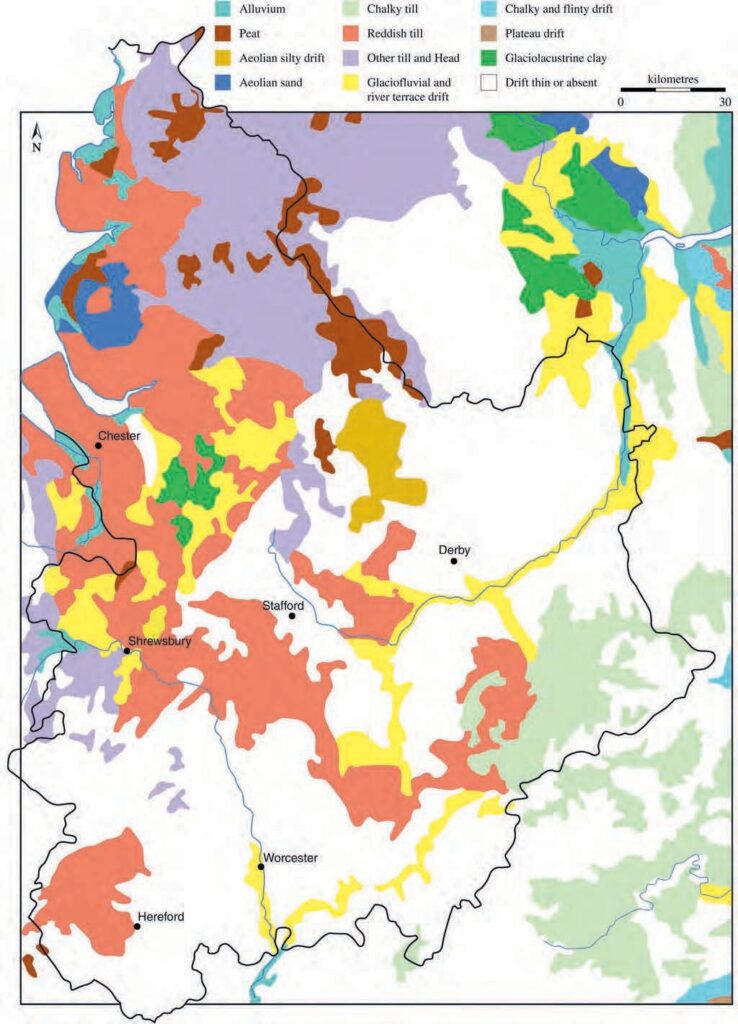

These provide evidence for approximately 400 million years of Earth history and a continental drift from about 40-50 degrees south of the equator, to southern Britain’s present position within the northern, temperate climatic belt. Accordingly the geology of the West Midlands provides evidence for large-scale climatic change through time (Anderton et al 1979; Duff and Smith 1992; Ellis et al 1996; Woodcock and Strachan 2000). Quaternary deposits, ranging from glacial clays, sands and gravels to river terrace deposits, solifluction deposits and modern river alluvium, locally mantle these rocks (Wills 1948; Hains and Horton 1969; Earp and Hains 1971; Ragg et al 1984; Keen 1989; Fig 1.2).

Sedimentary rocks dominate the West Midlands. Igneous and metamorphic rocks occur locally, as within the Precambrian terrains of the Malvern Hills and the Church Stretton area (Fig 1.3). In essence, the West Midlands area divides the substantially post-Carboniferous, weakly deformed geological terrain of the east midlands from the highly-folded and faulted Lower Palaeozoic terrain of mid Wales (British Geological Survey 2001).

Precambrian terrains have locally undergone considerable geological deformation. For instance, the late Precambrian Malvernian rocks of the Malvern Hills and the Rushton schists of the Church Stretton area, have suffered varying degrees of metamorphism, locally resulting in high-grade schistose and gneissic metamorphic rock types, while the late Precambrian Longmyndian rocks of the Longmynd, Shropshire, for example, are less deformed and include sandstones, mudstones and volcanic ashes.

The well-preserved Lower Palaeozoic marine successions of the region are dominated by sandstone, shale and limestone, deposited on the stable basement of the Midland Platform and in adjacent parts of the Welsh Basin. These are developed for example in the Welsh Borderland, Black Country inliers (eg Wren’s Nest, Dudley) and the Nuneaton Inlier of northern Warwickshire. These strata have yielded many invertebrate fossils, indicating marine environments ranging from shallow-water reef settings to deep-sea basins, between around 540 and 415 million years before present.

The West Midlands were only mildly deformed by a major episode of Earth movement and deformation in mid Silurian-early Devonian times – the so-called ‘Caledonian Orogeny’. This remarkable event resulted from the closure of the Iapetus Ocean, causing the collision of ‘Scotland’ and ‘England’ and the Caledonian mountain-building episode. Following this, the Devonian Old Red Sandstone of the Welsh Borderland comprises a thick pile of predominantly red sandstones and mudstones, deposited largely on arid river floodplains to the south of the eroding Caledonian foothills, at about 15-20°S latitude. The Old Red Sandstone contains abundant evidence of early non-marine life, notably the remains of primitive freshwater fish.

Limestones of Lower Carboniferous age are well developed in parts of Staffordshire and the Welsh Borderland. They originated as lime-rich muds and sands, shell and coral banks in a clear, tropical sea that flooded the area north of the Midland Platform during an early Carboniferous sea-level rise. Overlying the Carboniferous Limestone, the Millstone Grit is especially well developed in North Staffordshire as coarse-grained sandstones interbedded with shales. These were deposited as part of a complex of deltas that invaded the Carboniferous sea. The Upper Carboniferous Coal Measures Group is known from the Wyre Forest, Coalbrookdale, Shrewsbury, North Staffordshire, South Staffordshire and Warwickshire Coalfields. These economically important strata originated as mud, sand and peat, deposited in and around hot, humid equatorial swamps, lakes and river floodplains roughly 300 million years ago. They are overlain by the so-called ‘Barren Measures’ of late Carboniferous age – poorly fossiliferous, predominantly red-coloured mudstones, sandstones and conglomerates that are mainly of semi-arid alluvial origin.

The West Midlands area underwent gentle folding and faulting during the Variscan mountain-building episode, which peaked during the Upper Carboniferous and into the early Permian. This resulted from the continent of Gondwana moving northwards against Laurussia, to form the ‘supercontinent’ of Pangaea. The West Midlands area was additionally affected by extensive faulting during the early part of the Permian Period, attributable to regional stretching of the continental crust in response to early opening of the Atlantic Ocean. Much of the Permian and Triassic succession of the West Midlands accumulated among the resultant terrain of hills and rift valleys. Permian strata are well developed in Warwickshire and the Bridgnorth area of Shropshire, comprising reddish mudstones, sandstones and conglomerates, laid down in hot, arid conditions, at approximately 10-20°N latitude. Amongst these, the thick Bridgnorth Sandstone (Fig 1.4) includes the remains of large-scale aeolian (wind-blown) sand dunes.

Triassic strata are more extensively developed in the region. A lower, sandy and pebbly succession (Sherwood Sandstone Group) is widespread, and includes the well-known Bunter Pebble Beds that are seen, for example, on Cannock Chase, Staffordshire. The so-called ‘Bunter’ quartzite pebbles are widespread in the West Midlands, either derived directly from Triassic pebble beds or recycled via Quaternary deposits. They are thought to have been derived ultimately from the ancient Armorican massif of Brittany-Cornwall. The Sherwood Sandstone Group is overlain by the Mercia Mudstone Group – rather featureless, unfossiliferous red mudstones (formerly known as ‘Keuper Marl’) enclosing thin sandstones such as the Arden Sandstone of Worcestershire and Warwickshire. The Permian and Triassic rocks were deposited partly in semi-arid environments, ranging from alluvial fans to wind swept salt flats. The very youngest Triassic rocks (Penarth Group) include black shales (Westbury Formation) and thin limestones (Langport Member) of marine origin.

Overlying the Triassic, Jurassic rocks are well developed in Worcestershire and Warwickshire but are also known from the Prees outlier of Shropshire. The Lower Jurassic is dominated by the mudstone-dominated successions of the Lias Group, interspersed with sandstones and ironstones. Middle Jurassic ‘Cotswold’ limestones of the Inferior Oolite and Great Oolite groups represent the youngest ‘solid’ geology of the

West Midlands area. The Jurassic strata are almost wholly of marine origin, deposited in a shallow epicontinental sea of subtropical aspect that covered much or all of the West Midlands, at latitudes of between 30° and 40°N.

During the Quaternary Period a range of unconsolidated clays, sands and gravels was deposited. During glacial phases, ice invaded the West Midlands from the Welsh Mountains, Irish Sea, southern Scotland, Pennines and Vale of York, introducing varied suites of erratic pebbles amongst the boulder clays and fluvio-glacial sands and gravels. Post-glacial river terrace deposits, consisting mainly of sand and gravel, are widespread in the modern river valleys. Amongst the most recent geological deposits, alluvium forms modern river floodplains. Peat deposits locally occur, both in lowland and upland settings. The mosses and meres of North Shropshire and Staffordshire are a series of water or peat-filled hollows. They originated as ‘kettle holes’ – flooded topographic depressions representing the sites of melted ice blocks. Shropshire’s northern plain is additionally characterised by ranges of glacial morainic hills and smaller drumlins. Variation throughout the region in underlying geology, landscape, climate and vegetation has given rise to a wide variety of soil types.

The West Midlands region is topographically varied, though predominantly a lowland area below 250m above sea level. The harder, commonly older rock formations, give rise to upland areas such as the Malvern Hills and the Shelve district and Longmynd of Shropshire. The Black Mountain escarpment, Herefordshire, is composed of a thick Devonian Old Red Sandstone succession and rises to more than 600m above sea level. Upper Carboniferous (Coal Measures) rocks produce varied topography, including the subdued, rolling topography of the Warwickshire Coalfield, the dolerite-capped upland of the Clee Hills, Shropshire, and the higher ground of the western Peak District. The extensive outcrops of Triassic Mercia Mudstone form low-lying country, as in North Shropshire. Sandstone outcrops that locally give rise to landscapes of low hills and incised valleys vary the Mercia Mudstone lowlands. The Lower Jurassic Lias Group clays and thin limestones form low-lying agricultural vales, fringed by escarpments, plateaux and outlying hills formed by the sandstones and ironstones of the Dyrham Formation and Marlstone Rock Formation, and the Middle Jurassic Cotswold limestones of the Inferior Oolite and Great Oolite groups. Such outcrops characterise Warwickshire and Worcestershire’s Cotswold fringe. Post-glacial and Recent deposits, including terrace gravels and alluvium, are widespread features of modern river valleys.

Historically, the area has been central to the early development of geological science. The historic and scientific importance of geological sites in the West Midlands is underpinned by the Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) network, protected and administered by Natural England. Pioneers such as Robert Plot (1640-1696), John Farey (1766-1826) and William Smith (1769-1839) are all associated with the region. Sir Roderick Murchison, a former Director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, provided a detailed account of the geology of Staffordshire, Worcestershire and Shropshire in ‘The Silurian System’, published in 1839. Eminent 19th-century palaeontologists such as Richard Owen founded studies on locally collected fossils. The Geological Survey initiated systematic geological mapping in the 19th century. ‘Old Series’ one inch maps have been superseded by the ‘New Series’, currently published at 1:50,000 scale. The maps have been accompanied by a series of sheet memoirs, providing comprehensive detail of surface and subsurface geology. Other eminent field geologists who have worked in the region include Charles Lapworth (1842-1920), Leonard Wills (1884-1979), and Fred Shotton (1906-1990).

Rock, fossil and mineral specimens from the West Midlands have been dispersed into recognised collections throughout Britain and beyond. Notable amongst these are the Silurian invertebrate faunas of the Welsh Borderlands and the Black Country, Coal Measures plants, and Triassic-Jurassic vertebrates. Local collections, including important holdings of West Midlands specimens, are listed in Appendix 1.1. The rocks of the West Midlands contain strata of considerable economic importance, notably coal, limestone, ironstone, building stone, brick clay, cement materials, gypsum, salt, sand and gravel. Intensely industrialised areas have consequently developed, notably the Black Country

and The Potteries. Ironbridge Gorge, the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, owes its significance to locally available deposits of coal, clay, limestone and iron ore.

Acknowledgements

Paul Smith (School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham) and Don Steward (The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery) commented on an early version of the text.

Appendix 1.1: Local geological collections

The West Midlands Natural Science Collections Group provides information and advice on geological collections within the region. Further details are available on their website at: www.naturalsciencewm.org.uk

The following collections are especially rich in local material:

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Chamberlain Square, Birmingham B3 3DH, tel. 0121 303 2834, www.bmag.org.uk

Major strengths of the collection include Palaeozoic and Mesozoic rock and fossil specimens from the West Midlands.

Dudley Museum and Art Gallery, St James’s Road, Dudley DY1 1HU, tel. 01384 815575, www.dudley.gov.uk

Includes a comprehensive collection of Wenlock and Ludlow (Silurian) fossils from the Dudley and Walsall areas. There are also representative specimens from the local Coal Measures, including fossil plants and remains of terrestrial animals.

The Lapworth Museum of Geology: University of Birmingham, Edgbaston B15 2TT, tel. 0121 414 7924/4173, www.lapworth.bham.ac.uk

The collections include fossils, rocks and minerals from the midlands region, including the archive collection of Charles Lapworth.

Ludlow Library and Museum Resource Centre, Parkway, Ludlow SY8 2PG, tel. 01584 813666, www.shropshireonline.gov.uk/llmrc.nsf

Includes a comprehensive collection of fossil and rocks from the Palaeozoic rocks of south Shropshire and the Welsh Borders, and Shropshire mammoths.

Stoke-on-Trent: Potteries Museum and Art Gallery, Bethesda Street, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent ST1 3DE, tel. 01782 232323, www.stoke.gov.uk/museums

The collection is notably rich in locally collected Carboniferous and Triassic rocks and fossils. Highlights include Coal Measures fish and local minerals.

Warwickshire Museum, Market Place, Warwick CV34 4SA, tel. 01926 412500, www. warwickshire.gov.uk/museum

Strengths include locally collected Triassic and Jurassic fossils.